Peak Airplanes

the plane truth

related page:

www.resilience.org/stories/2016-02-16/how-far-can-we-get-without-flying

I’m a climate scientist who doesn’t fly. I try to avoid burning fossil fuels, because it’s clear that doing so causes real harm to humans and to nonhumans, today and far into the future. I don’t like harming others, so I don’t fly. Back in 2010, though, I was awash in cognitive dissonance. My awareness of global warming had risen to a fever pitch, but I hadn’t yet made real changes to my daily life. ...

However, the total climate impact of planes is likely two to three times greater than the impact from the CO2 emissions alone. This is because planes emit mono-nitrogen oxides into the upper troposphere, form contrails, and seed cirrus clouds with aerosols from fuel combustion. These three effects enhance warming in the short term. (Note that the charts in this article exclude these effects.)

Given the high climate impact, why is it that so many environmentalists still choose to fly so much? I know climate activists who fly a hundred thousand miles per year. ...

In the post-carbon future, it’s unlikely that there will be commercial plane travel on today’s scale. Biofuel is currently the only petroleum substitute suitable for commercial flight. In practice, this means waste vegetable oil, but there isn’t enough to go around. In 2010, the world produced 216 million gallons of jet fuel per day but only about half as much vegetable oil, much of which is eaten; leftover oil from fryers is already in high demand. This suggests that even if we were to squander our limited biofuel on planes, only the ultra-rich would be able to afford them.

note from Mark: there's a consortium in Washington State trying to figure out how to turn trees into jet fuel, which would radically accelerate deforestation (and therefore, climate chaos).

http://holmgren.com.au/why-i-havent-been-flying-much/

Why I haven't been flying (much)

by David Holmgren on May 16, 2013

plane truth about flying and climate

www.chooseclimate.org (flying off to a warmer climate)

www.cartome.org/9-11climatology.htm

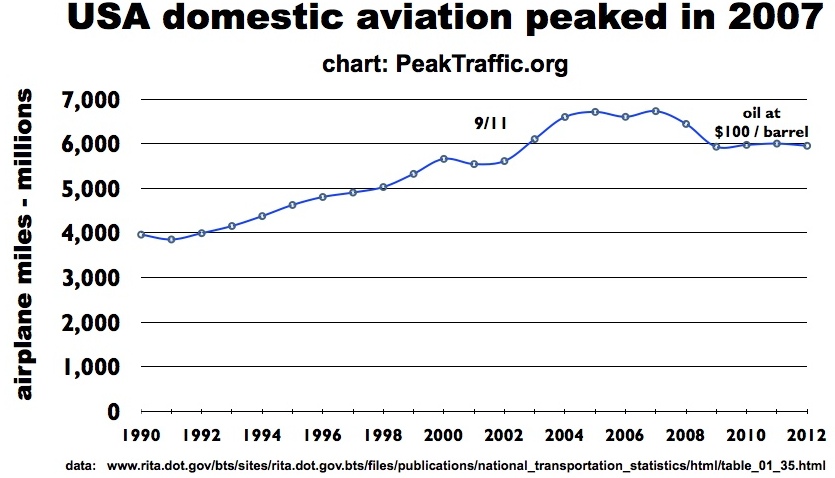

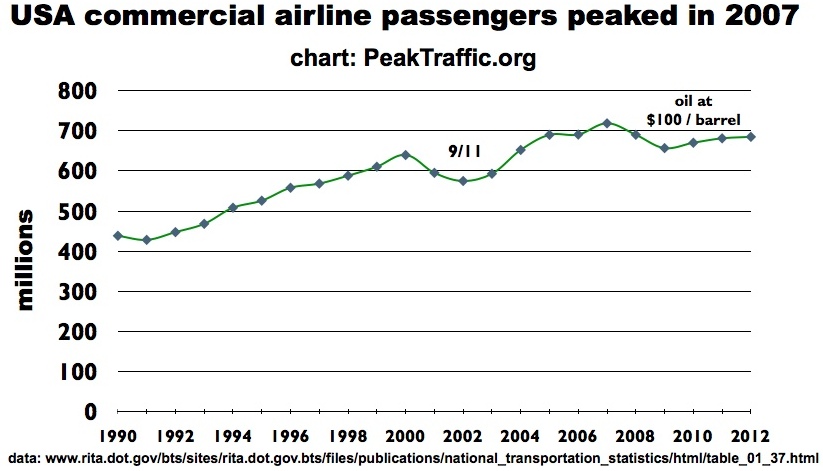

Peak Air Travel

www.fcnp.com/national_commentary/the_peak_oil_crisis_the_half-life_for_air_travel_20080501.html

In recent weeks, airlines around the world have been reporting substantial losses, declaring bankruptcy or completely shutting down. So far the losses have been mostly of small airlines, but many of the large ones have started to thrash around for merger partners. At $3.71 a gallon, jet fuel is now the single largest expense an airline faces.

In 2000, the airlines fuel bill was $14 billion. It is now pushing $60 billion and climbing. Southwest, the most profitable carrier, recently announced that this year’s fuel bill will be $500 million more than last year and equal to 2007 profits. During the first quarter of 2008 American airlines lost $328 million; Delta lost $274 million; United lost $537 million; Continental $80 million; Northwest $191 million; and US Airways $236 million. Only Southwest Airlines, which did a better job of hedging its fuel than the others, made a profit.

It is clear we are going to see major changes in air travel shortly.

www.globalpublicmedia.com/saying_goodbye_to_air_travel

Saying Goodbye to Air Travel

14 May 2008

by Richard Heinberg

The airline industry has no future. The same is true for airfreight. No air carrier has a viable plan to make a profit with oil at current prices—much less in years to come as the petroleum available to world markets dwindles rapidly.

That’s not to say that jetliners will disappear overnight, but rather that the cheap flights we’ve seen in the past will soon be fading memories. In a few years jet service will be available only to the wealthy, or to the government and military.

Sir Richard Branson of Virgin Atlantic says he wants to use biofuels to power his fleet of 747’s and Airbuses. There are still some bugs to be worked out in terms of basic chemistry, but it might be possible in principle—if only we could make enough biodiesel or ethanol without further driving up food prices and wrecking the soil. Even then it would be very costly fuel.

Are there other options for powered flight?

Hydrogen could be burned in jet engines, but doing so would require a complete redesign of our commercial aircraft fleet, and H2 would be expensive to make—unless the growing trend toward more costly electricity (as we phase out depleting, polluting coal and increasingly scarce natural gas) can somehow be reversed.

Last year I was invited to give the keynote address at the world’s first Electric Aircraft Symposium. NASA and Boeing sent representatives, but all told there were only about 20 in attendance. The planes being discussed were ultralight two-seaters: that’s the limit of current or foreseeable battery technology. These might come in handy in a future where they are the only option for emergency air travel (blimps need depleting helium or explosive hydrogen). But forget about 300-seat planes running on solar or wind power, ferrying middle-class vacationers to Bali or Venice.

There are good reasons to cut down on air travel voluntarily: flying not only swells our personal carbon emissions but spews CO2 and other pollutants into the stratosphere, where they do the most damage. However, the worsening scarcity of the stuff we use for making jet fuel takes the discussion out of the realm of optional moral action and into that of economic necessity and personal adaptation.

I fly to educate both general audiences and policy makers about fossil fuel depletion; in fact, I’m writing this article aboard a plane en route from Boston to San Francisco. I wince at my carbon footprint, but console myself with the hope that my message helps thousands of others to change their consumption patterns. This inner conflict is about to be resolved: the decline of affordable air travel is forcing me to rethink my work. I’m already starting to do much more by video teleconference, much less by jet.

Those who live far from family will be more than inconvenienced, as will the hundreds of thousands who work for the airline industry directly or indirectly, or the millions who depend on tourism or airfreight for an income. These folks will have few options: teleconferencing can accomplish only so much.

Our species’ historically brief fling with flight has been fun, educational, and enriching on many levels to those fortunate enough to benefit from it. Saying goodbye will be difficult. But maybe as we do we can say hello to greater involvement in our local communities.

Toronto Star

www.thestar.com/News/Ideas/article/471491

The End of Travel

High oil prices are crippling airlines and travellers alike and we may only be at the start of a new, global class divide between the stranded and the mobile

Aug 02, 2008

NICOLE BAUTE

High oil prices are crippling airlines and travellers alike and we may only be at the start of a new, global class divide between the stranded and the mobile.

In Europe's late medieval period, the labouring masses rarely travelled further than a few dozen miles from where they were born. For them, travel was dangerous, onerous and slow.

But wealthy aristocrats travelled far and wide in the name of diplomacy, meeting leaders from other countries and extending their power and influence.

For Steven Flusty, an associate professor of geography at York University, this is what society could once again look like if predictions that the lower-middle classes will no longer be able to afford to fly in just a few years come true.

It would be tremendously debilitating and could wind up "breaking down everything below a certain class level, where they are being held in space as if it's some kind of a container," he says.

The North American airline industry is under siege, with exorbitant fuel costs, a slowing economy and competition from Asia and the Middle East leading to employee layoffs and flight reductions.

Within a year or two, insists writer James Howard Kunstler and others, it will all be over. They predict the demise of the commercial airline industry as it currently exists.

And then, like in the medieval age, society will split into two groups: the mobile, and the stranded. [...]

www.walrusmagazine.com/print/2008.07-travel-grounded-travel-by-air-david-beers/

Grounded

Imagining a world without flight

by David Beers

Walrus magazine, Toronto, Ontario, Summer 2008 issue

I remember being very young in the family backyard in California, looking skyward with my father at the passing airplanes. He helped me learn each shape, assigning names and purposes: transport, airliner, fighter. Before I was born, he had piloted a fighter jet, and he would tell stories of tearing up the heavens with his friends, of signing out a Grumman F9F-8 in the morning, flying more than 1,500 kilometres to have dinner with his parents, then climbing back into his cockpit the next morning and returning to base, six tonnes of kerosene fuel and a weekend well burned.

Air travel has lost most of its mystique in the half century since, but that does not make the fact of mechanical flight any less impressive. On a sunny day, at the end of runway 26R at Vancouver International Airport, you may find a half-dozen people enjoying the spectacle of a 363,000-kilogram jumbo jet surfing the air. I show up on a misty and brooding morning, and because the wind is blowing out to sea, the airliners come and go on the other side of the airport. They sound like receding thunder. The tall grass whips and shivers. I am alone. It’s easy to imagine a day, maybe not so far off, when the number of jets in the sky will have dwindled dramatically. A time when such huge birds might again seem exotic.

Could it happen? As the potential ravages of global warming come more solidly into view, jet travel has been fingered as a dangerous emitter of greenhouse gases. And now the price of oil is said by various experts to be headed toward $200 (US) a barrel within the year, maybe five, a sign for many that we’ve entered a new age of fossil fuel scarcity. What if we come to decide jet travel has become too polluting to risk our children’s future? Or just far too expensive to continue flying the kids to Disneyland?

And if a million such decisions were to cause the jet age to end, how would we come back to earth? Softly, one would hope. Pleasantly. But maybe, instead, it will be a white-knuckle crash.

George Monbiot, Guardian columnist and author of the 2006 bestseller Heat: How to Stop the Planet from Burning, wants a forced landing — immediately. Jet travel, he states, is “the greatest future cause of global warming.” And people who fly are “killers.”

At present, aviation accounts for only about 2 percent of total human carbon emissions, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. But because jets fly so high, their effect on global warming is near-tripled. Monbiot calculates that the industry is growing so fast that within decades jet travel will erase most potential climate-friendly gains in other sectors.

The European Union has responded by including aviation in its carbon emissions trading scheme as of 2012. Next year, the United Kingdom will charge a carbon tax on all flights within and out of the country. Here in North America, neither approach is close at hand. British Columbia’s “cutting-edge” carbon tax will apply to flights inside the province but not those with outside connections. And jet fuel itself can’t be taxed by any nation; international trade agreements prevent it.

Some airlines will let you choose to spend more to buy carbon offsets, but such volunteer programs aren’t likely to give the planet’s thermostat much of a shove. After a year of offering the option, Air Canada reports its passengers bought a mere $131,529 in carbon offsets, worth a puny 1,644 trees. People might step up to buy a lot more carbon offsets if the “messaging” were better and “fully integrated into the ticket purchasing experience,” says Joe Kelly, director of environmental services for InterVistas, a Canadian firm that consults for airline and tourism companies. His survey shows that “people need to feel confident their money is really going to make a difference.” He adds, “Of course, a lot of people say one thing and do another.”

He also points out that Boeing will soon roll out its carbon-fibre-bodied 787 Dreamliner, said to be 20 percent more fuel efficient than its predecessors. And an April press release from the International Air Transport Association trumpeted “a historic commitment to tackle climate change” and a vision for “a carbon emission free industry.”

Monbiot takes no solace from any of it. The window on defeating global warming is closing rapidly, and governments must ground the fleets now. Like an angry preacher who has glimpsed hellfire, he spreads his gospel. “When I challenge my friends about their planned weekend in Rome or their holiday in Florida,” he writes, “they respond with a strange, distant smile and avert their eyes . . . The moral dissonance is deafening.” He’s not the only one championing the latest environmental commandment: thou shalt not fly. “Making selfish choices such as flying on holiday,” preaches the bishop of London, Richard Chartres, is “a symptom of sin.”

Yes, perhaps. But business is booming. As the middle classes of China and India take to the sky, the global airline industry expects passengers to double to 9 billion in twenty-five years. If this comes to pass, even aviation’s most optimistic expectation of further carbon emission cuts, admits Kelly, will be more than wiped out by humanity’s enthusiasm for air travel. It would seem Monbiot is pretty much on the money.

Where he may be wrong, however, is in taking the air industry’s growth projections seriously. Long before global warming punishes us for our sins, aviation will crash for a different reason: too little kerosene fuel. So say those who believe world oil production is very near, or at, its peak. On the other side of that peak, every barrel of oil becomes more expensive to pull out of the ground, even as demand rises. The result will be runaway fuel prices and, ultimately, the restructuring of our economies, whether we are ready or not.

Roger Bezdek — co-author of a famous 2005 report on peak oil for the United States Department of Energy, and president of Management Information Services, which consults with government agencies and power utilities — doesn’t believe the aviation industry’s “sky’s the limit” growth projections. “Officially, they have to say that to protect their stock values and equipment sales.” But some airline execs have confided to him they are working on Plan B: surviving the inevitable peak oil shakeout when fuel prices go through the roof and the industry shrinks.

“If people have to decide between driving to their jobs or taking a vacation, which will they choose?” Bezdek asks rhetorically. The ripple effect, he predicts, will beggar public treasuries and devastate communities. “Across North America and worldwide, every region, state, country, is betting the farm on the growth of the airline industry — financing infrastructure, business parks, convention centres. That’s hundreds of millions of dollars of infrastructure.”

He expects, in twenty-five years, the “seedy” deterioration of hotel zones around overbuilt, underused airports. “Vegas is going to grind to a halt. Orlando, Vail, Aspen — destination resort areas will get a lot fewer customers.” If you aren’t rich, you won’t fly much, if at all. Priorities will be different, starker. More fossil fuel will instead be burned to “handle social dissension, unrest.”

The idea of a world without flight poses somewhat of a predicament to someone like Dr. Angus Friday of Grenada, a tiny Caribbean island nation assumed to be below the main hurricane belt — until two massive storms wracked the tiny nation, in 2004 and 2005. In his role as chair of the forty-four-member Alliance of Small Island States, Friday flies around the world, urging action against climate change, and aid for countries like his in bracing for rising sea levels and increasingly violent storm surges. Yet the day I catch up with him on the phone from somewhere in India, he gently reminds me that jetliners bring the tourists to the beaches, and that tourism is Grenada’s main source of revenue, so he is in no position to instruct sinners to stay home. “The real challenge is to release some of the entrepreneurial forces that can create solutions to climate change.” And peak oil, presumably.

Friday prefers to place his faith in human ingenuity. He cites, as many do, Virgin Atlantic Airways owner Richard Branson, who recently proved one of his airliners could fly on 20 percent ethanol blended with the usual kerosene, and who has invested $1 billion (US) in developing alternative energy sources, including biofuels from non-food plant waste.

Growing crops for biofuels is one of those green ideas that seems to have come and gone in barely a year’s time. The pressure it was expected to put on agricultural land helped send food commodity prices soaring this spring. Studies reported in the New York Times find biofuel cultivation would actually accelerate climate change.At the far fringe of the field, some optimistic researchers have proposed creating vast algae ponds in empty deserts to make biodiesel from the muck. So far, Branson has been cryptic about what Virgin Fuel will be, except to boast, “It is 100 percent environmentally friendly, and I believe it’s the future of fuel. Over the next twenty or thirty years, I think it actually will replace the conventional fuel that you get out of the ground.”

“Richard Branson,” says James Howard Kunstler, author of The Long Emergency: Surviving the End of Oil, Climate Change, and Other Converging Catastrophes of the Twenty-First Century, “is suffering from the delusion of techno-triumphalism. In fact, he is close to being off his rocker about this.” No airline is going to escape the “liquid fuels problem,” he says, referring to the fact that US civil aviation is expected to consume half the country’s oil production by 2030.

Kunstler suggests that Branson may have pulled off a small “stunt,” but that “it doesn’t scale.” Mass production of enough biofuel to feed aviation is just not possible. In any case, in a few years competition for access to every form of fuel will be chaotically fierce. Passing the global oil production peak will trigger, as his book foretells, “an unprecedented economic crisis that will wreak havoc on national economies, topple governments, alter national boundaries, provoke military strife, and challenge the continuation of civilized life.

“Commercial airlines will probably fail within the next five years,” Kunstler declares. Spiking fuel costs are already causing carriers to cut other operating costs to the bone. “Look, we saw four small airlines go out of business in just the past ten days.”

If Kunstler isn’t buying what Branson is selling, many of us do yearn for it. Sir Richard, with his boyish enthusiasm for balloons and jets and private rocket ships, is the latest in a long line of public figures who’ve exploited the obvious metaphor of flight as human ascent, progress. He bids us not to lose faith in the heavens and our dominion over them.

The airplane was the streamlined shape of the twentieth century, a war-spawned creation that, as Le Corbusier wrote, “mobilized invention, intelligence and daring, imagination and cold reason. It is the same spirit that built the Parthenon.” If so, what new shapes, born of a similar spirit, might replace it?

On the Internet, I find images of helium-filled Zeppelins with exotic curves, luxurious staterooms, haughty observation decks. Their designers expect them to be propelled by combinations of fuel-efficient diesel motors, small jet turbines, the sun, and the wind. The Manned Cloud, designed by Jean-Marie Massaud with the French national aerospace research body onera, is intended to carry forty guests across 5,000 kilometres in about thirty hours, and is shaped like a beautiful white whale. There are also the sleek, electric-driven 250-kilometre-an-hour bullet trains already in operation in Europe and Asia; and, nearly twice as fast, the world’s first superconducting magnetic levitation train, purchased for $1.2 billion (US) from German engineers to ferry travellers between Shanghai and its airport. Japan is planning to pour $100 billion (US) into an even faster maglev train to run between Tokyo and Osaka. Technically it will fly, if just a few inches above the ground.

But this is not the future envisioned by Kunstler, who I begin to think enjoys picking the wings off humans. “It’s a mistake to imagine that the years ahead are all about leisure and recreation and we can just substitute one form for another. We are going to be living in a far less affluent society.” By then, one imagines, what’s left of the legions of business warriors striding through airports today will instead be cooped up watching video screens in teleconferencing centres. But for must of us, the business at hand will be working the land. The way we produce and transport food now is extremely fossil fuel intensive. As peak oil makes air travel a remote luxury, says Kunstler, our eyes must revert downward, toward the soil.

To this child of the jet age, it all seems a terribly hard landing. I phone my father, who retired from his aerospace engineering career long ago but still pilots a propeller-driven airplane he shares with a flying club. Can you imagine a world without air travel? I ask him. Do you think about it?

“Yes, I think about it often. And I can imagine you may see it in your lifetime. What made the airplane and jet travel possible was oil, pure and simple. And now, as our oil supply inevitably diminishes, we are entering the end of a natural cycle. Right now, those people in those aluminum tubes at 30,000 feet are there because they can be, not because they need to be.

“We will adapt,” he says, after a pause, “or not, I guess.” And he laughs.

- Published July 2008David Beers is the founding editor of the Tyee and author of Blue Sky Dream: A Memoir of America's Fall from Grace.