Peak Oil News

www.peakoil.net/Newspapers/Aarticles.html

www.lifeaftertheoilcrash.net/Articles.html

www.lifeaftertheoilcrash.net/BreakingNews.html

www.truthout.org/docs_04/083004A.shtml

Get Ready for the Peak Experience

By Kelpie Wilson

t r u t h o u t | Perspective

Monday 30 August 2004

When history looks back, 2004 will turn out to be a remarkable

year, and not just for the unraveling of the lies and deceits of the Bush

presidency. Equally as significant is the emergence into public prominence

of certain scientific facts that have long been suppressed.

Two new realities are fast converging on the public consciousness

with what may be serendipitous timing: climate change and peak oil. After

years of controversy and denial, there finally seems to be a solid consensus

that climate change is here, it threatens everything from agriculture

to human health, and it will probably turn out to be even worse than predicted.

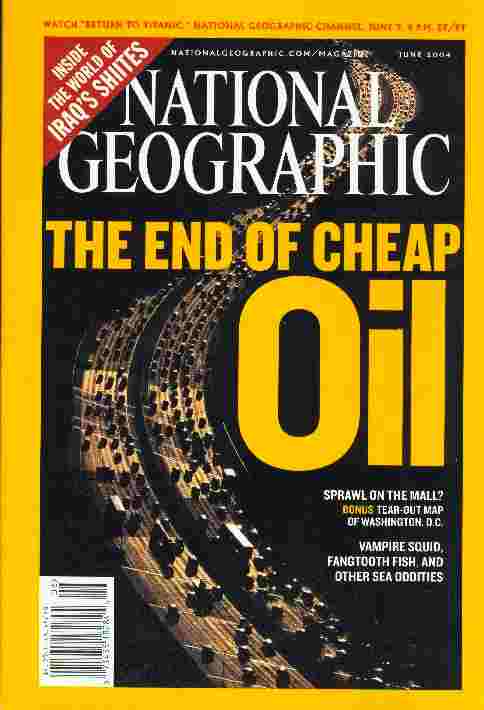

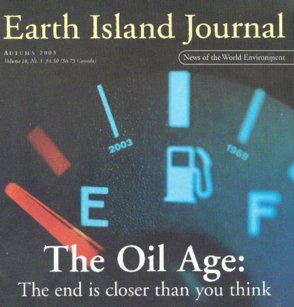

Peak oil is a still obscure term you will soon be hearing

a lot more about. It simply refers to the peak of oil production. Oil

was made over millions of years as ancient life was crushed and buried

under the earth, and they ain't making any more of it - at least not on

any timescale that is meaningful to us - so like any limited commodity

(think Picasso paintings or antique porcelain), the supply will rise to

meet demand and then begin to fall. As supply falls, prices will go up,

perhaps drastically.

Like a hiker climbing through clouds, we can't know where

the peak is until we reach it and feel the ground falling away beneath

our feet. But wait -- why are there clouds? Why can't we see the peak

before we get there? Don't we have monitoring agencies that exist to make

predictions about things like when the oil supply will peak?

As far as the average consumer and SUV buyer is concerned,

the climb has been a stairway to heaven. The coming decline in oil production

is something rarely mentioned in public, and when it is, it is portrayed

as something so impossibly far off in the future that there is no sense

in talking about it. The obscuring clouds have been deliberately generated

by a collusion of oil industry, financial and government interests. They

don't want us to know that we are about to fall off the world as we know

it.

So I was mildly shocked to hear Texas oilman and corporate

raider, T. Boone Pickens declare on NPR's Morning Edition last week: 'The

peak is now.'

Pickens is certainly not the last word on peak prediction,

but other serious analysts come close to his views. Petroleum geologist

Kenneth Deffeyes, author of the breakthrough book 'Hubbert's Peak,' predicts

the peak will fall on Thanksgiving Day in 2005. Others are more reluctant

to pinpoint the peak and say it may be a few more years yet, but certainly

before 2010. That's five, six years at the most to get our ducks in a

row and ready to face a world of vastly accelerating oil prices.

Contrast this news with what governments and oil companies

and have been saying. According to the US Energy Information Agency, oil

production won't peak until 2035.

On the corporate side, British Petroleum publishes an annual

Statistical Review of World Energy that is widely cited. Responding directly

to the critics who point to an early peak, Lord Browne, chief executive

for British Petroleum wrote in the latest edition of the Review that:

"At current levels of consumption, there are sufficient reserves

to meet oil demand for some 40 years and to meet natural gas demand for

well over 60 years." There is no acceleration of oil depletion, he

maintained.

But last week the Energy Institute of London released an independent

analysis of BP's data showing that total world production declined by

1.14 million barrels a day last year. On top of that, the analysis found

that the annual rate of decline is accelerating.

Oil companies do not want the word to get out. On August 24th,

Shell Oil agreed to pay a $150 million fine for inflating its proven reserves

by 4.5 billion barrels. Shell is the third largest oil company in the

world and one fifth of their stated reserves were a lie. They did it to

protect their stock value.

From the perspective of climate change, news that oil is peaking

sooner rather than later is good news. We need to end the fossil fuel

addiction anyway, and only higher oil prices will tilt the economics in

favor of solar, wind and other renewables.

But we have got ourselves in a very dangerous situation. The

potential exists for oil prices to increase quickly and radically. There

won't be much time to manufacture the new energy infrastructure. Belt

tightening will be needed. Economies could turn to dirty coal for a quick

energy fix and the competition for the remaining oil could heat up into

further wars.

For this reason, accurate widely disseminated information

about energy is absolutely critical. At all costs, we must not allow the

media game that went on with global warming to happen with peak oil.

A recent study ('Balance as Bias: Global Warming and the U.S.

Prestige Press,' in Global Environmental Change) examined coverage of

global warming in prestigious newspapers such as the New York Times and

the Washington Post. The study found that these 'papers of record' responded

to industry propaganda campaigns to discredit global warming by regularly

setting up a handful of industry trained critics as 'balance' against

the larger scientific consensus. Confusion reigned in the public mind,

and a precious decade was lost.

Now Gaia is asserting herself. Seas are turning acid, corals

bleaching; vapors and smoke are bleeding into the stratosphere where all

is not well with the ozone skin. Massive forest fires, storms, floods

and heat waves are waking people up. When the news comes in through your

window, or tears off your roof - TV turns irrelevant.

This newfound awareness of global warming will be of great

help as we attempt to quickly map out the path to a new energy future.

As we climb down from the peak, the way is perilous and uncertain. There

will be a temptation to go all out for extracting oil and gas from heavy

oil shales, tar sands and coal. This will only dig us deeper into the

global warming hole. Knowing that the hole is there will help keep us

on the straight and narrow path to a truly renewable society based on

solar, wind, hydro, tidal and biomass.

The new energy economy will be diffuse as different technologies

are used to harvest the energy resources particular to each region. Solar

and wind are low density energy sources and we will have to work harder

for our energy. Oil's high energy density is what makes it possible for

a handful of men to control it and the politics and economy of the world.

Many will wail and cry that the end of oil means the end of

the American Dream. It could mean that, but only if we let it. The American

Dream is not the endless accumulation of stuff and sprawl. The American

Dream is not empire without end and the garrison state. The American Dream

is freedom and the pursuit of happiness.

For too long, we and the world have been chained to the petro-dollar.

New possibilities await. Let us go forward not in fear, but in the spirit

of adventure.

Kelpie Wilson is the t r u t h o u t environment editor. A

veteran forest protection activist and mechanical engineer, she writes

from her solar-powered cabin in the Siskiyou Mountains of southwest Oregon.

http://story.news.yahoo.com/news?tmpl=story&u=/dowjones/20040308/bs_dowjones/200403080046000016

Business - Dow Jones Business News

Former Shell Chairman Was Told of Reserve Issues

Mon Mar 8,12:46 AM ET LONDON -- The ousted chairman of Royal Dutch/Shell

(NYSE:RD - News) Group was warned of possible overstatements in the oil

titan's petroleum reserves two years before he publicly disclosed them,

two people familiar with the situation told The Wall Street Journal.

A memo, circulated to Sir Philip Watts and other senior executives in

early 2002, warned that the company's method of booking oil and natural-gas

reserves appeared to be inconsistent with U.S. Securities and Exchange

Commission (news - web sites) guidelines, these two people said. The memo

pointed out that the company might have to revise downward its reserve

tally by the equivalent of about one billion barrels of oil, these people

said.

On Jan. 9, the world's third-largest publicly traded oil company by market

value announced it would cut its oil and natural-gas reserves by about

20%, or 3.9 billion barrels of oil equivalent. A good chunk of the overbooking

occurred during Sir Philip's tenure as the companywide head of exploration

and production between 1997 and 2001. He became chairman in 2001.

Just taking the oil portion, the reclassified reserves represent $67.5

billion of potential future revenue, assuming moderate oil prices of $25

a barrel. The SEC since has launched a formal investigation into the matter.

Last week, the twin Dutch and British boards of the company ousted Sir

Philip and a top deputy. The move came after Shell's audit committee briefed

directors about preliminary findings into the reserve revisions conducted

by an internal team of investigators and outside counsel. The team found

a "trail of communications" showing Sir Philip appeared to have

known about longstanding internal questions over the validity of the reserves

bookings, according to one of the people familiar with the situation.

Wall Street Journal Staff Reporters Chip Cummins, Bhushan Bahree in New

York and Susan Warren in Dallas contributed to this article.

http://csmonitor.com/2004/0129/p14s01-wogi.html

From the January 29, 2004 edition

Has global oil production peaked?

By David R. Francis | Staff writer of The Christian Science Monitor

Today's civilization depends on an abundant and relatively cheap supply

of oil. It fuels most of our vehicles, aircraft, ships, and trains. It

provides the raw material for fertilizer, some clothing fabrics, most

plastics, and many chemicals. Oil heats many of our homes and businesses.

So when experts discuss when oil production will begin to decline, the

world pays heed. The question now making the rounds in energy circles:

Has production already peaked?

If it has - or if a peak lies only a few years away - the repercussions

would be huge. It could intensify a scramble by oil importers to tie up

existing reserves. Decline could lead to scarcity and higher prices, possibly

recession, while prompting an urgent push to alternative fuels and conservation.

For at least one analyst, the scenario has already begun to unfold.

"World production is flat now," says Kenneth Deffeyes, a Princeton

University geology professor.

But that's a controversial view. Other pessimists talk about 2010; many

analysts see no change until 2035.

Of course, various "experts" have been predicting the end of

the oil age for more than 100 years. And even now, no one really knows

how much oil is left in the ground. Estimates involve guesses of not only

future oil finds but future world economic output and oil consumption.

These numbers are typically highly imprecise.

Even calculating current reserves is tricky. The Royal Dutch/Shell Group,

one of the world's largest oil producers, shocked the financial community

earlier this month when it announced it had overbooked its proven reserves

by 20 percent - an indication of the fragility of such estimates.

The United States Geological Survey (USGS) puts yearly world consumption

of oil today at about 30 billion barrels. That comes out of known or proven

world reserves of 1.1 trillion barrels, according to IHS Energy, an oil

and gas information-gathering group in Tetbury, England. By adding in

Canada's oil sands, the Oil and Gas Journal in Houston raises proven reserves

to 1.266 trillion.

"It is not an issue in which there are absolute answers," says

Robert Tippee, editor of the Houston trade journal. Much depends on advancing

technology and the economics of production, as well as how much oil the

ground really holds.

Advocates of a production peak coming soon offer several pieces of evidence:

• Total world oil production reached 68 million barrels per day

in 2003, according to a count by the Oil and Gas Journal. That's not much

above the 66.7 million barrels per day. in 2001. Oil reserves estimated

at 1.266 trillion are up only a bit from 1.213 trillion a year earlier.

• Production has peaked for more than 50 oil-producing nations,

including the US (1970) and Britain (1999). China, second to the US in

the consumption of oil, was a net exporter of oil until five years ago.

• The Department of Energy predicts world demand will reach 119

million b.p.d. in 2025, with huge increases in China, India, and other

developing nations.

• In 2002, the world used four times as much oil as was newly found.

• The rate of discovery of worldwide oil reserves, after declining

for 40 years, has slowed to a trickle. In 2000, there were 16 large discoveries

of oil, eight in 2001, three in 2002, and none last year, notes James

Meyer, director of the Oil Depletion Analysis Centre in London.

• All the giant fields, such as those in the Middle East, have already

been discovered, some experts say. These giants are relatively easy to

find. The last major oil field, Cantarell, off Mexico's shore, was discovered

in 1976.

"The oil companies are drilling fewer and fewer wells," says

Colin Campbell, founder of the Association for the Study of Peak Oil,

a network of scientists, professors, and government experts. "There

are fewer worthwhile prospects to test."

But optimists see another picture.

For example, with scientific advances, oil companies have boosted their

drilling success, which means they don't need to drill as many wells.

Last year, nearly 40 percent of exploration and wildcat projects located

oil, gas, or gas condensate, according to IHS Energy.

Besides conventional oil, there are huge amounts in Canadian oil sands,

Venezuelan heavy oils, and Rocky Mountain shale. If oil prices skyrocket,

oil in deep offshore fields and in polar regions would become economically

feasible to extract. And there's oil from natural gas, which experts see

as lasting longer than conventional oil, outside North America.

The USGS added the oil sands to the world's reserves recently, making

Canada the second-largest holder of reserves after Saudi Arabia. These

sands are already being exploited. But they require the injection of hydrogen

to make their tar oil light enough to flow in a pipe.

Meanwhile, estimates of oil reserves keep growing. For example, world

oil reserves now are five times as great as at the end of World War II,

says Thomas Ahlbrandt, chief of the USGS World Energy Project. And they

grew 15 percent in the past five years - without adding in the Canadian

oil sands - mostly by upgrading the proven reserves in existing fields.

The world has used up about 930 billion barrels of oil since the 1800s,

and has left some 3 trillion in the ground. That estimate includes about

732 billion barrels of not-yet-discovered oil and an assumed growth in

reserves in already discovered fields, the USGS reckons. So by now, the

world has used up about 23 percent of its total available petroleum resource,

Mr. Ahlbrandt calculates. Most people using USGS numbers figure world

oil output will flatten in 2036-37, he adds. But non-OPEC oil output could

peak between 2015 and 2020.

"I can see no peak for the next 20 or 30 years," says energy

consultant Michael Lynch. Since Mr. Lynch has been a keen critic of such

early-peak advocates as Mr. Campbell, setting even such a not-so-far-away

date is seen as a concession of sorts.

In any case, major oil importers aren't waiting around to find out who's

right. The US, Japan, Europe, and China, are scrambling to tie down petroleum

resources in the Caspian Sea region, Russia, West Africa, Iraq, Iran,

and Libya.

Japan and China are competing for access to Russia's little-tapped Far

East oil resources. China, which expects a quintupling of its oil needs

by 2030, wants a new pipeline to go from Angarsk in Russia to inland Daqing

in its northeastern industrial heartland. Japan proposes the pipeline

go rather to Vostochny, on the shore near Vladivostok. One reason Japan

is sending 500 soldiers to Iraq this month is to stabilize Middle Eastern

oil, the source of 90 percent of Japan's oil, Japan's defense minister,

Shigeru Ishiba, told the Financial Times last month.

Pundits say the US has been especially interested in the recent election

in Georgia to replace President Eduard Shevardnadze because that nation,

though not having reserves itself, is the corridor for a $3 billion pipeline

through which huge supplies in Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, and Kazakhstan

must pass through to reach the West. A Chinese oil firm last month embarked

on its first international venture by buying a 50 percent stake in a Kazakhstan

oil field.

The US has just extended trade preferences to Angola, where oil giants

ChevronTexaco and ExxonMobil are preparing to spend billions of dollars

on deep-water developments. Other US oil firms, such as ConocoPhillips,

Occidental Petroleum, Marathon Oil, and Amerada Hess are looking carefully

at their prospects for returning to Libya should the US government lift

sanctions on that desert nation.

According to a New York Times report, a step that put Russian oil mogul

Mikhail Khodorkovsky in jail was his plan to sell a major stake in his

oil company, Yukos, to ExxonMobil. US oil firms would like to invest more

in Russia's oil and gas reserves, if they can negotiate that country's

legal and political minefield.

The competition for oil resources not fully under contract is expected

to get rougher. It could be especially crucial for consumers in North

America, who on average use up more than their body weight in crude oil

each week.

Many experts suspect that oil was one reason, among others, the US invaded

Iraq. America's longstanding concern with its oil supplies is nothing

new. Newly declassified British documents suggest that President Nixon

was prepared as a "last resort" to launch airborne troops to

seize oil fields in Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and Abu Dhabi to end the 1973-74

oil embargo on the US by the Arab nations.

Some countries - even some oil firms - have decided to invest in solar

and wind energy. "This reflects the realization that exploring for

large new sources of oil is not a realistic way to go," says Mr.

Meyer.

Mr. Deffeyes says the US should have stepped up its research on alternative

energies 15 years ago. But others don't see a crisis looming just yet.

Certainly nations should be researching better sources of energy, says

Mr. Lynch. "But it should not be based on imminent scarcity."

The Guardian (London) -- December 1, 2003

www.guardian.co.uk/comment/story/0,3604,1097622,00.html

Bottom of the barrel

The world is running out of oil - so why do politicians refuse to talk

about it?

By George Monbiot

The oil industry is buzzing. On Thursday, the government approved the development of the biggest deposit discovered in British territory for at least 10 years. Everywhere we are told that this is a "huge" find, which dispels the idea that North Sea oil is in terminal decline. You begin to recognise how serious the human predicament has become when you discover that this "huge" new field will supply the world with oil for five and a quarter days.

Every generation has its taboo, and ours is this: that the resource upon which our lives have been built is running out. We don't talk about it because we cannot imagine it. This is a civilisation in denial.

Oil itself won't disappear, but extracting what remains is becoming ever more difficult and expensive. The discovery of new reserves peaked in the 1960s. Every year we use four times as much oil as we find. All the big strikes appear to have been made long ago: the 400m barrels in the new North Sea field would have been considered piffling in the 1970s. Our future supplies depend on the discovery of small new deposits and the better exploitation of big old ones. No one with expertise in the field is in any doubt that the global production of oil will peak before long.

The only question is how long. The most optimistic projections are the ones produced by the US department of energy, which claims that this will not take place until 2037. But the US energy information agency has admitted that the government's figures have been fudged: it has based its projections for oil supply on the projections for oil demand, perhaps in order not to sow panic in the financial markets.

Other analysts are less sanguine. The petroleum geologist Colin Campbell calculates that global extraction will peak before 2010. In August, the geophysicist Kenneth Deffeyes told New Scientist that he was "99% confident" that the date of maximum global production will be 2004. Even if the optimists are correct, we will be scraping the oil barrel within the lifetimes of most of those who are middle-aged today.

The supply of oil will decline, but global demand will not. Today we will burn 76m barrels; by 2020 we will be using 112m barrels a day, after which projected demand accelerates. If supply declines and demand grows, we soon encounter something with which the people of the advanced industrial economies are unfamiliar: shortage. The price of oil will go through the roof.

As the price rises, the sectors which are now almost wholly dependent on crude oil - principally transport and farming - will be forced to contract. Given that climate change caused by burning oil is cooking the planet, this might appear to be a good thing. The problem is that our lives have become hard-wired to the oil economy. Our sprawling suburbs are impossible to service without cars. High oil prices mean high food prices: much of the world's growing population will go hungry. These problems will be exacerbated by the direct connection between the price of oil and the rate of unemployment. The last five recessions in the US were all preceded by a rise in the oil price.

Oil, of course, is not the only fuel on which vehicles can run. There are plenty of possible substitutes, but none of them is likely to be anywhere near as cheap as crude is today. Petroleum can be extracted from tar sands and oil shale, but in most cases the process uses almost as much energy as it liberates, while creating great mountains and lakes of toxic waste. Natural gas is a better option, but switching from oil to gas propulsion would require a vast and staggeringly expensive new fuel infrastructure. Gas, of course, is subject to the same constraints as oil: at current rates of use, the world has about 50 years' supply, but if gas were to take the place of oil its life would be much shorter.

Vehicles could be run from fuel cells powered by hydrogen, which is produced by the electrolysis of water. But the electricity which produces the hydrogen has to come from somewhere. To fill all the cars in the US would require four times the current capacity of the national grid. Coal burning is filthy, nuclear energy is expensive and lethal. Running the world's cars from wind or solar power would require a greater investment than any civilisation has ever made before. New studies suggest that leaking hydrogen could damage the ozone layer and exacerbate global warming.

Turning crops into diesel or methanol is just about viable in terms of recoverable energy, but it means using the land on which food is now grown for fuel. My rough calculations suggest that running the United Kingdom's cars on rapeseed oil would require an area of arable fields the size of England.

There is one possible solution which no one writing about the impending oil crisis seems to have noticed: a technique with which the British and Australian governments are currently experimenting, called underground coal gasification. This is a fancy term for setting light to coal seams which are too deep or too expensive to mine, and catching the gas which emerges. It's a hideous prospect, as it means that several trillion tonnes of carbon which was otherwise impossible to exploit becomes available, with the likely result that global warming will eliminate life on Earth.

We seem, in other words, to be in trouble. Either we lay hands on every available source of fossil fuel, in which case we fry the planet and civilisation collapses, or we run out, and civilisation collapses.

The only rational response to both the impending end of the oil age and the menace of global warming is to redesign our cities, our farming and our lives. But this cannot happen without massive political pressure, and our problem is that no one ever rioted for austerity. People tend to take to the streets because they want to consume more, not less. Given a choice between a new set of matching tableware and the survival of humanity, I suspect that most people would choose the tableware.

In view of all this, the notion that the war with Iraq had nothing to do with oil is simply preposterous. The US attacked Iraq (which appears to have had no weapons of mass destruction and was not threatening other nations), rather than North Korea (which is actively developing a nuclear weapons programme and boasting of its intentions to blow everyone else to kingdom come) because Iraq had something it wanted. In one respect alone, Bush and Blair have been making plans for the day when oil production peaks, by seeking to secure the reserves of other nations.

I refuse to believe that there is not a better means of averting disaster than this. I refuse to believe that human beings are collectively incapable of making rational decisions. But I am beginning to wonder what the basis of my belief might be.

· The sources for this and all George Monbiot's recent articles can be found at http://www.monbiot.com/

www.bbc.co.uk/business/programmes/moneyprogramme/archive/oil.shtml

The advocates of war insist it's not about oil. But global oil production

is on the brink of terminal decline and when the West begins to run short

of supplies - Iraq could be a lifeline.

Wednesday 26 March 2003 - 7.30pm BBC2

It's not greed that’s driving big oil companies - it's survival. The rate of oil discovery has been falling ever since the 1960's when 47 billion barrels a year were discovered, mostly in the Middle East.

In the 70's the rate dropped to about 35 billion barrels while the industry concentrated on the North Sea. In the 80's it was Russia’s turn, and the discovery rate dropped to 24 billion. It dropped even further in the 90's as the industry concentrated on West Africa but only found some 14 billion barrels.

Shrinking production

In America, always the greediest consumer of oil, production has been falling for 30 years. Americans guzzle 20 million barrels of oil a day, but now they have to import over 60% of it.

North Sea oil rig That pattern is being repeated elsewhere. Geologist Dr Colin Campbell predicted a decline in the North Sea several years ago and claims by 2015 Britain may have to import over half its oil needs. "In 1999 Britain went over the top and is declining quite rapidly," he says.

"It's now 17% down in just three years, and this pattern is set to continue. That means that Britain will soon be a net importer, imports have to rise, the costs of the imports have to rise, and even the security of supply is becoming a little uncertain," Campbell adds.

In Norway the government forecasts that in the next ten years its North Sea production will halve. In Argentina oil production has been down for several years and in Columbia, which was a big producer in the 90's, production is now past its peak.

US energy security

When George Bush took power two years ago, his administration was already worried about the vulnerability of America’s oil supplies - the buzzword was ‘energy security’.

"I think it’s quite possible that the United States realises the key importance of the Middle East generally to world supply in fact, and especially its own, and that it sees Saddam Hussein as a ready-made villain," points out Campbell. ....

For a war supposedly not about oil, military planners made a high priority of securing the oilfields. Apart from a handful of wells torched by Iraqi troops, the huge southern oilfields were taken largely intact. But other major oil-producing regions are still in Iraqi hands and there is still a danger that, as in Kuwait 12 years ago, massive sabotage may hit oil production for years to come.

Terminal decline

Whatever happens, rebuilding Iraq will be a huge job and only US companies have been invited to bid for contracts.

Opposition leader Dr Salah Al-Shaikhly, of the Iraqi National Accord, admits Britain and America will benefit from helping remove Saddam. "Well definitely those who have helped us, all along, with regime change. Obviously they should have a little edge over the rest. I think even in economics, this is quite acceptable… as well as the politics."

But even if Iraq does boost its oil production ironically the effect could be short lived. Its vast reserves represent just four years of world consumption and by the time Iraqi oil is flowing freely, global oil production may already be in terminal decline.

Campbell thinks the decline will start by 2010. "It starts with a price shock due to control of the market by a few countries, and it is followed by the onset of physical shortage, which just gets worse and worse and worse," he says.

So if alternatives to oil are not found soon the changes could be radical. Unlimited use of cars and cheap flights around the world may well be a thing of the past. While international trade - the very basis of the global economy - will suffer.

http://www.melbourne.indymedia.org/news/2004/01/59989.php

Plan now for a world without oil

by Michael Meacher

January 5 2004, Financial Times. The former UK environment minister with

a chilling warning about life on the down slope of oil depletion. (Michael

Meacher stepped down from the Blair government in protest in June)

Four months ago, Britain's oil imports overtook its exports, underlining a decline in North Sea oil production that was already well under way. North Sea oil output peaked at about 2.9m barrels per day in 1999, and has been predicted to fall to only 1.6m bpd by 2007. Even the discovery of the new Buzzard field, the biggest British oil find in a decade, with a total of some 500m barrels recoverable, will not alter by much the overall picture of dwindling resources.

This prospect would not be so bleak were it not that similar trends are now becoming manifest around the globe. The three main oil-producing regions are Opec, the former Soviet Union, and the rest of the world. According to papers presented at the latest annual meetings of the Association for the Study of Peak Oil, Opec's future production is expected to peak in 2020 at about 40-45m bpd. Under-production in the former Soviet Union in the 1990s has been followed by a new surge in east Siberia and Sakhalin. Together with new discoveries in the Caspian, this will yield a peak of about 10m bpd in 2010.

Combining the models for Opec, the former Soviet Union and the remaining 40 or more major oil-producing countries puts ultimate world oil recovery - past and future - at some 2,200bn barrels, with production peaking at about 80m bpd between 2010 and 2020. To this may be added non-conventional oil and other liquids brought into commercial production by the rising price as oil becomes more scarce. These include oil from coal and shale, bitumen and derived synthetics, heavy and extra-heavy oil, deep-water oil, polar oil and liquids from gas fields and gas plants. These sources, though at very much greater cost, could provide an ultimate recovery of about 800bn barrels and might peak in 2050 at around 20m bpd. But the combined model suggests a peak from all sources of about 90m bpd around 2015.

Today we enjoy a daily production of 75m bpd. But to meet projected demand in 2015, we would need to open new oilfields that can give an additional 60m bpd. This is frankly impossible. It would require the equivalent of more than 10 new regions, each the size of the North Sea. Maybe Iraq with enormous new investments will increase production by 6m bpd, and the rest of the Middle East might be able to do the same. But to suggest that the rest of the world could produce an extra 40m barrels daily is just moonshine.

These calculations place the coming oil crunch some time between 2010 and 2015, perhaps earlier. The reserves in the world's super-giant and giant oilfields are dwindling at an average rate of 4-6 per cent a year. No more big frontier regions remain to be explored except the north and south poles. The production of non-conventional crude oil has already been initiated at enormous cost in Venezuela's Orinoco belt and Canada's Athabasca tar sands and ultra-deep waters. Yet no major primary energy alternative can replace oil and gas in the short-to-medium term.

The implications of this are mind-blowing, since oil provides 40 per cent of all traded energy and no less than 90 per cent of transport fuel. But not only are the motor vehicle and farming industries dependent on oil, so is national defence. Oil powers the vast network of planes, tanks, helicopters and ships that provide the basis of each country's armaments. It is hard to envisage the effects of a radically reduced oil supply on a modern economy or society. Yet just such a radical reduction is staring us in the face.

The world faces a stark choice. It can continue down the existing path of rising oil consumption, trying to pre-empt available remaining oil supplies, if necessary by military force, but without avoiding a steady exhaustion of global capacity. Or it could switch to renewable sources of energy, much more stringent standards of energy efficiency, and a steady reduction in oil use. The latter course would involve huge new investment in energy generation and transportation technologies.

The US response to this dilemma is very striking. The National Energy Policy report prepared by Dick Cheney, US vice-president, in May 2001 proposed the exploitation of untapped reserves in protected wilderness areas within the US, notably the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge in north-eastern Alaska. The rejection of this extremely contentious proposal forced President George W. Bush, unwilling to curb America's ever-growing thirst for oil, to go back on White House rhetoric and accept the need to increase oil imports from foreign suppliers.

It was a fateful decision. It means that, for the US alone, oil imports, or imports of other sources of oil, such as natural gas liquids, will have to rise from 11m bpd to 18.5m bpd by 2020. Securing that increment of imported oil - the equivalent of total current oil consumption by China and India combined - has driven an integrated US oil-military strategy ever since.

There is, however, a fundamental weakness in this policy. Most countries targeted as a source of increased oil supplies to the US are riven by deep internal conflicts, strong anti-Americanism, or both. Iraq is only the first example of the cost - both in cash and in soldiers' lives - of facing down resistance or fighting resource wars in key oil-producing regions, a cost that even the US may find unsustainable.

The conclusion is clear: if we do not immediately plan to make the switch to renewable energy - faster, and backed by far greater investment than currently envisaged - then civilisation faces the sharpest and perhaps most violent dislocation in recent history.

The writer was UK environment minister from 1997 to June 2003

http://politics.guardian.co.uk/iraq/comment/0,12956,1036687,00.html

"This war on terrorism is bogus: The 9/11 attacks gave the US an

ideal pretext to use force to secure its global domination"

Michael Meacher, Saturday September 6, 2003, The Guardian

(environment minister for "poodle" Tony Blair from 1997 to 2003,

Member of the British Parliament)

The overriding motivation for this political smokescreen is that the US and the UK are beginning to run out of secure hydrocarbon energy supplies. By 2010 the Muslim world will control as much as 60% of the world's oil production and, even more importantly, 95% of remaining global oil export capacity. As demand is increasing, so supply is decreasing, continually since the 1960s.

http://abcnews.go.com/sections/SciTech/DyeHard/oil_energy_dyehard_040211.html

Dried Up?

Are We Running Out of Oil? Scientist Warns of Looming Crisis

By Lee Dye

Special to ABCNEWS.com

Feb. 11— "Civilization as we know it will come to

an end sometime in this century unless we can find a way to live without

fossil fuels."

That's the way David Goodstein begins his book. And that's the way he

ends it.

Goodstein is not an environmental extremist, or a doomsayer, or a political

hack trying to make points with his constituency. He is a professor of

physics and vice provost of the California Institute of Technology, one

of the nation's headiest institutions.

In his just-released book, Out of Gas: The End of the Age of Oil, published

by W. W. Norton & Company, Goodstein argues forcefully that the worldwide

production of oil will peak soon, possibly within this decade. That will

be followed by declining availability of fossil fuels that could plunge

the world into global conflicts as nations struggle to capture their piece

of a shrinking pie.

We've all heard that before, only to be told by organizations like the

U.S. Department of Energy that there's plenty of oil around, much of it

still undiscovered, and there's no cause for panic. Some economists argue

that as the supply declines, the price will rise, making it possible to

develop energy sources that are not now available, such as the mineral

rich oil sands of Canada, or the shale formations in the western United

States.

Clues From a Historical Rebel

Some time soon we'll find out who's right, but Goodstein argues that we

don't have any time to spare. It takes decades to develop new energy sources,

as the prestigious National Academy of Sciences warned last week in a

report on the dream of using hydrogen to fuel our cars. So are we poised

to meet this challenge head on?

Not likely, Goodstein says.

"Nothing is going to happen until we have a crisis," he said

in an interview. "When we have a crisis, I think attitudes will change."

That crisis, he predicts, will probably come sooner rather than later.

But how can experts from economics and science and business differ so

strongly on an issue that is this important? How can they look at the

same data and come to such different conclusions?

Most predictions concerning the end of the age of oil are based on estimates

of when the supply will run out and the last drop is pulled from the last

well. But that's the wrong way to look at it, Goodstein argues.

Goodstein relies partly on the work of a historical rebel in the oil industry,

M. King Hubbert. Back in the 1950s, when Hubbert was working as a geophysicist

with Shell Oil Company, he predicted that oil production in the United

States would peak by 1970.

He was almost laughed out of his profession, but guess what? He turned

out to be right.

U.S. Oil production has been declining ever since, leading to an increased

reliance on foreign oil, and we all know where that has led.

Hubbert's formula was really pretty simple. He looked at all the geological

reports that were available at that time and determined how much oil nature

had created for us beneath the United States. Then he determined how much

had been extracted. He found that half of it would be gone by 1970, and

U.S. production would decline forever thereafter.

Best- and Worst-Case Scenarios

Globally, nature left about 2 trillion barrels beneath the ground, and

the peak will occur when we reach the halfway point, Goodstein argues.

Since we have used close to a trillion barrels, the peak can't be more

than a few years away, he says. But are huge new oil fields waiting out

there somewhere to be discovered?

"Better to believe in the tooth fairy," he writes.

Most of the planet has been explored extensively, and even if some new

fields are found, they won't delay the peak by more than a few years,

he says.

So that leads him to two scenarios.

"Worst case: After Hubbert's peak, all efforts to produce, distribute,

and consume alternative fuels fast enough to fill the gap between falling

supplies and rising demand fail. Runaway inflation and worldwide depression

leave many billions of people with no alternative but to burn coal in

vast quantities for warmth, cooking, and primitive industry. The change

in the greenhouse effect that results eventually tips Earth's climate

into a new state hostile to life. End of story.

"Best case: The worldwide disruptions that follow Hubbert's peak

serve as a global wake-up call. A methane-based economy is successful

in bridging the gap temporarily while nuclear power plants are built and

the infrastructure for other alternative fuels is put in place. The world

watches anxiously as each new Hubbert's peak estimate for uranium and

oil shale makes front-page news."

A number of things can be done, but all have some limitations, and all

take the one thing we're running out of — time.

"There can't be a quick resolution," Goodstein said in the interview.

"It's a huge problem."

Time to Switch?

He would begin an immediate shift toward a greater reliance on natural

gas, since supplies of methane are greater

than the remaining oil, and he sees no alternative to building more nuclear

power plants. That won't sit well with many Americans.

"There are difficulties and dangers associated with nuclear power,

but there may be no alternative," he writes. Other potential sources

of energy, like oil shale, are fraught with environmental problems and

they may take more energy to develop than they ultimately produce.

That has been the case in other fields, including fusion reactors that

could make their own fuel.

Despite the fact that the federal government has poured billions into

fusion research, no experimental reactor has ever produced more energy

than it consumes, not even for a second.

Ultimately, Goodstein argues, we must return to the energy source used

by our ancestors thousands of years ago.

"There is a cheap, plentiful supply of energy available for

the taking," he says, and we won't run out of it for billions of

years. "It's called sunlight."

Therein lies the greatest hope. New technological breakthroughs could

finally harness the sun in ways we haven't even begun to imagine. But

it will take a commitment on a global scale that would make the Manhattan

Project seem like child's play.

And here we are in the midst of a presidential election campaign, and

no one is even talking about it.

Lee Dye’s column appears weekly on ABCNEWS.com. A former science writer for the Los Angeles Times, he now lives in Juneau, Alaska.

http://www.fromthewilderness.com/free/ww3/111403_shell_oil.html

Shell announces closure of refinery in Bakersfield

Thursday, November 13, 2003

URL: http://www.sfgate.com/cgibin/article.cgi?file=/news/archive/2003/11/13/state1622EST0100.DTL&type=printable

(11-13) 13:22 PST FRESNO, Calif. (AP) --

Shell Oil Products announced Thursday it will close down a refinery in

Bakersfield next year because of the decreasing supply of crude oil in

the area, company officials said.

The refinery, which has been in Bakersfield for 70 years and employs 215

people, depends on availability of San Joaquin Heavy Crude to make gasoline,

gas oil, butane and other products.

Now reports from the California Department of Conservation and the California

Energy commission have shown that the local supply of petroleum is going

down, and the refinery will no longer be economically viable, company

representatives said.

"The decision to close the facility was by no means an easy one,"

Aamir Farid, the General Manager of Shell's Bay-Valley Complex, said.

"Shell recognizes that this refinery has served as an integral component

of the community for nearly 70 years. However, the fact remains that there

is simply no longer an adequate supply of crude oil to justify the continued

operation of this facility."

The refinery's products were used in the southern San Joaquin Valley and

the Central Coast, but the company is working to avoid any disruption

in supply to the area. Officials said they could not predict what effects,

if any, the October 2004 closure would have on gas prices in the valley.

©2003 Associated Press

http://www.forbes.com/business/newswire/2004/01/09/rtr1204985.html

Major oil stocks fall as Shell restates reserves

Reuters, 01.09.04, 11:28 AM ET By Joseph A. Giannone

NEW YORK (Reuters) - Shares of major oil companies fell Friday after Royal

Dutch/Shell Group shocked investors by slashing its "proven"

reserves by 20 percent.

News of the revision triggered concerns that other producers may also

have improperly booked reserves as "proven" -- a category comprising

oil and gas from developed and undeveloped fields that companies believe

can be extracted and sold profitably under current market conditions.

Shell shifted 3.9 billion barrels of reserves previously listed as "proven"

into two less valuable categories -- "unproven" or having "scope

for recovery." The announcement revealed excessive optimism for key

areas including Australia's giant Gorgon gas field, onshore activities

in Nigeria and other unspecified areas in the eastern hemisphere.

New York-listed shares of Shell Transport and Royal Dutch Petroleum were

the second- and third-biggest loser on the New York Stock Exchange in

early trade, both falling more than 7 percent.

The only field Shell identified as a problem was Gorgon, an $8 billion

Australian development in which Shell has a stake, but where ChevronTexaco

Corp. is the operator.

Shares of ChevronTexaco fell 1.9 percent. Exxon Mobil Corp. , the world's

largest oil company, fell nearly 2 percent in early trade.

Analysts and company officials said they don't expect a wave of revisions

by U.S. oil producers.

"We are very confident in our proved reserves numbers and stand behind

them," Exxon Mobil spokesman Tom Cirigliano said. "They meet

all S.E.C. regulations and guidelines. We're very conservative and we

have a very structured, deliberate process in moving reserves into the

proved reserves category."

Chevron officials were not immediately available to comment on reserves

accounting. (Additional reporting by Melanie Cheary, Sudip Kar-Gupta,

Andrew Callus and Andrew Mitchell in London)

Copyright 2004, Reuters News Service

May 8, 2004, 12:05AM

http://www.chron.com/cs/CDA/ssistory.mpl/business/energy/2557282

Coal supplies dwindle at U.S. power plants

By STEVE JAMES

Reuters News Service

NEW YORK — Coal supplies at U.S. power plants are at their lowest

levels in more than three years, sparking concern of possible blackouts

this summer when demand is heavy for electricity to power air conditioners.

CoalPeople.com, a coal industry newsletter, said supplies may be 10 percent

to 20 percent lower than at this time last year, while National Mining

Association experts believe that on average, coal-fired American plants

have probably 40 to 45 days' supply compared with the 60 to 90 days' supply

that was normal in the 1990s.

Just last month, Peabody Energy Chairman and Chief Executive Officer Irl

Engelhardt said reliability might become an issue at some plants, while

hot weather in Southern California this week once again highlighted how

close America lives to an energy disaster like last August's monster blackout

in New York and other eastern U.S. and Canadian cities.

"They are much lower than they have ever been for some time,"

said Connie Holmes, senior economist at the National Mining Association.

"You can only run down stockpiles so much. I am a bit surprised."

She said one reason for the reduction of coal supplies could be cost-cutting

associated with deregulation.

"They don't want to tie up so much money for so long," she said.

Other factors are that many utilities built up reserves after the 2000-2001

California energy crisis and recent rail problems have disrupted coal

deliveries in the East. In addition, recent high natural gas prices have

had utilities opting to use up their coal.

The issue is significant because 95 percent of U.S. produced coal is used

in U.S. power plants — just over 1 billion tons last year, Holmes

said. At the same time, coal comprises more than half of total U.S. generation.

Peabody Energy said last month that coal inventories at U.S. generators

were estimated at about 110 million tons, their lowest levels since February

2001.

Jon Cartwright, head of institutional research at BOSC, said he did not

know of a plant at risk of running out, "but at these kinds of price

levels you just don't replace your inventories so quickly.

"If you do in fact get the kind of economic recovery that the recent

numbers are suggesting and you get a hot summer, you are going to see

very high electric prices."

Richard Hunter, managing director of the global power group at Fitch Ratings,

said companies have been running down stockpiles in an efficiency drive.

The Alliance to Save Energy, a Washington-based advocacy group that encourages

individual consumers and energy producers to be more efficient, said the

blackout last August showed just how vulnerable the power grid might be.

"There is tremendous concern over the issue, to avoid possible blackouts,"

President Kateri Callahan said

www.thebulletin.org/issues/2004/jf04/jf04cavallo.html

January/February 2004, Volume 60, No. 1, pp. 20-22, 70

Oil: The illusion of plenty

By Alfred Cavallo

One hundred and twelve billion of anything sounds like a limitless quantity.

But in terms of barrels of oil, it's just a drop in the gas tank. The

world uses about 27 billion barrels of oil per year, meaning that 112

billion barrels--the proven oil reserves of Iraq, the second largest proven

oil reserves in the world--would last a little more than four years at

today's usage rates.

In the future, 112 billion barrels will likely prove even shorter-lived.

In the United States, gas-guzzling sport utility vehicles and larger homes

are deemed essential. As the underdeveloped world industrializes, demand

for oil by billions of people increases; China and India are building

superhighways and automobile factories. Energy demand is expected to rise

by about 50 percent over the next 20 years, with about 40 percent of that

demand to be supplied by petroleum.

Ever-increasing supplies of low-cost petroleum are thought to be vital

to the U.S. and world economies, which is why the invasion of Iraq and

the belief that controlling its 112-billion-barrel reserve would give

the United States a limitless pipeline to cheap oil were so dangerous.

The war in Iraq will definitely have an effect on the U.S. and world economies,

but not a positive one. The invasion, occupation, and rebuilding of Iraq

will cost the people of the United States both blood and treasure. But

more to the point, Iraq could be a fatal distraction from many fundamental

and extremely unpleasant facts that actually threaten the United States--one

of which is the finite nature of petroleum resources.

Petroleum reserves are limited. Petroleum is not a renewable resource

and production cannot continue to increase indefinitely. A day of reckoning

will come sometime in the future. The point at which production can no

longer keep up with increasing demand will mean a radical and painful

readjustment globally to everyday life.

In spite of that indisputable fact, people behave as if the global petroleum

supply is unending. Predictions of the exhaustion of oil reserves seem

to have lost all credibility. The public assumes that inexpensive oil

will be available essentially forever. The idea that petroleum resources

are finite and that petroleum production might peak in the near future

seems to have vanished from all discussions of energy policy in Congress,

in the press, and even among public interest groups.

This surreal situation is due to several factors. One, certainly, is that

pessimists have cried wolf too often. Forecasts of imminent shortages

of oil, food, and other natural resources are confounded by the enormous

display of material goods that envelops consumers in the West. For most

people, the market price of any commodity is what signals shortage or

plenty. Time and again, collapsing oil prices have succeeded rising oil

prices, leading to the belief that oil will always become cheap again.

That oil supplies are currently abundant and inexpensive and have been

for nearly 20 years, and that the models used to predict peak oil production

are not easy to understand, appear to ignore economic factors, and are

based on proprietary data, explain to some degree the present feeling

of permanent abundance.

In reality, the differential between petroleum production cost and market

price is so large that market price cannot be used as a measure of resource

depletion. For example, the variation in the average price of oil between

1998 ($10 per barrel) and 2000 ($24 per barrel) had nothing to do with

depletion of reserves and everything to do with an attempt to exercise

"market discipline" by the Organization of Petroleum Exporting

Countries (OPEC).

But the most important reason there seems to be an unending supply of

oil is the activity of non-OPEC producers. Oil production is immensely

lucrative. Large amounts of petroleum have been and will continue to be

produced outside the Middle East at costs that are very low, $5-$10 per

barrel, compared to the desired OPEC price range of $22-$28 per barrel.

The opportunity to realize extraordinary profits provides irresistible

pressure to produce as much oil as possible, as soon as possible.

Yet oil is a finite resource, and there are only so many places to look

for it. Sooner or later petroleum production will decline, so sooner or

later the prophets of depletion will be correct. The question then becomes:

Can a peak oil forecast be made that is useful to the petroleum industry

and to consumers, one that will alert them to the problems and allow for

a redeployment of resources?Answering that question requires an understanding

of why the world's rising petroleum needs are being met without skyrocketing

prices or supply shortages.

Everyone knows that the science and technology underpinning computers,

telecommunications, and medicine have advanced dramatically over the last

20 years. The proof is everywhere, from ever more powerful personal computers,

to increasingly sophisticated cell phones, to new medical imaging technologies

and pharmaceuticals.

Unknown to most people, however, advances in geological sciences and petroleum

technologies have been equally profound and dramatic. Since the 1970s,

plate tectonics has been providing a uniform framework for understanding

the geology of the Earth's surface (including petroleum formation). Much

as X-ray and nuclear magnetic resonance tomography examine structures

within the human body non-invasively, three-dimensional seismography now

allows potential oil-bearing formations to be evaluated in great detail.

Nuclear magnetic resonance probes are used to determine porosity and hydrocarbon

content as well as to estimate the permeability of these formations. Petroleum

deposits are being brought into production on the continental shelves

off Texas, Brazil, and West Africa in water up to 8,000 feet deep--areas

that were, until recently, inaccessible. Technological advances like sub-sea

terminals, directional drilling, and floating production, storage, and

offloading ships have been developed to exploit smaller, previously uneconomic

or unreachable deposits. Sophisticated science and technology coupled

with unparalleled profitability has provided the foundation for the wide

availability of oil.

Yet the same advances in geology and engineering that have provided consumers

with seemingly limitless petroleum also allow much better estimates to

be made of how much oil may ultimately be recovered. After a five-year

collaboration with representatives from the petroleum industry and other

U.S. government agencies, the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) completed

a comprehensive study of oil resources. The "USGS World Petroleum

Assessment 2000" is the first study to use modern science to estimate

ultimate oil resources. [1]

The importance of this assessment is difficult to overstate. Previous

world oil resource evaluations have ranged from crude "back-of-the-envelope"

calculations to estimates based on proprietary databases, and have often

lacked enough detail to allow a comparison between production and estimated

reserves. We now have credible, easily accessible long-term production

records and science-based resource estimates for all of the important

oil producing regions in the world--crucial for understanding how oil

production might evolve over time.

The USGS assessment allocates reserves to three separate and distinct

categories. The first is "proven reserves," or petroleum that

can be produced using current technology. The second category is "undiscovered

reserves"--oil deposits that are highly likely to exist based on

similar areas already producing oil. The third category is "reserve

growth" and represents possible production from extensions of existing

fields, application of new technology, and decreased well spacing in existing

fields. Oil in this last category can be extracted much less rapidly than

oil in the proven and undiscovered categories. (For purposes of determining

the approximate year of peak or constant output, the best that can be

hoped for is that all proven reserves are produced and all undiscovered

reserves are found and produced as rapidly as needed. Petroleum from reserve

growth, produced at much lower rates, can be ignored. According to the

USGS, it is available only to lengthen the period of peak production or

to reduce the decline in a field's output.)As of January 1, 1996, OPEC's

proven and undiscovered reserves amounted to about 853 billion barrels,

while similar non-OPEC reserves were 769 billion barrels, according to

the USGS assessment. Based on actual production patterns in many non-OPEC

oil producers, output can increase until there remains between 10 and

20 years of proven plus undiscovered reserves (as determined by the USGS),

at which point a production plateau or decline sets in, depending on the

reserve growth that is actually available.

Given that non-OPEC production rates are nearly twice as great as OPEC

rates, and assuming stable prices and 2 percent per year market growth,

non-OPEC production will reach a maximum sometime between 2010 and 2018

based on resource limitations alone (assuming complete cooperation of

producers and that all undiscovered oil is actually found and produced

as rapidly as needed). [2] Once this happens, OPEC will control the market

completely, and it is unlikely that production will increase much longer.

Yet this simplistic analysis is too optimistic. There is no such thing

as "non-OPEC oil," but rather U.S. oil, Norwegian oil, and oil

produced by various other countries. In particular, about 39 percent of

non-OPEC proven plus undiscovered reserves are located in the former Soviet

Union. It is only a matter of time before these countries reach an agreement

with OPEC on how to divide the oil market, at which point the current

illusion of unlimited oil resources will end, not due to resource constraints

but to political factors.

Yet the U.S. public, industrial and political leaders, environmentalists,

and policy-makers in general do not believe that they need to be concerned

with the finite supply of oil and its unfavorable (from the U.S. perspective)

geographic distribution. As noted earlier, the overwhelming majority behaves

as if inexpensive oil will be readily available far into the distant future.

This attitude is reflected in U.S. policy toward Iraq. One might expect

that a major consequence of the U.S. conquest of Iraq would have been

full control of Iraqi oil reserves, reducing or eliminating the ability

of OPEC to set prices, and giving the United States a permanent--because

oil is forever--overwhelming strategic advantage. It would allow the United

States to dictate production rates and lower prices, which would serve

two important aims. Reduced prices would reward consumers in the West,

buying their support for U.S. policies. It would also deprive oil producers

of the revenues with which they could challenge the U.S. domination of

the Middle East. Oil prices could be expected to drop to between $15 and

$20 per barrel once existing Iraqi fields were refurbished and large new

deposits were developed.

However, lower prices would stimulate consumption and decrease the incentive

to develop more inaccessible reserves, essentially those of the non-OPEC

producers. If non-OPEC producers fail to develop those harder-to-get-at

reserves, peak oil production will more likely occur earlier, at the front

end of the 2010-2018 forecast. So the very success of the current effort

to seize control of the Middle East would doom U.S. imperial ambition

to failure within the next 10 years, from an oil supply standpoint.

This scenario is now implausible given the bitter Iraqi resistance to

U.S. occupation, and it is not clear when Iraqi production might reach,

much less significantly exceed, its pre-invasion level. To understand

what may unfold, given current levels of sabotage and chaos in Iraq, one

must examine how the petroleum marketing system has changed over the past

year, and in particular the role that OPEC producers have played.

In 2002, Iraqi oil production averaged two million barrels per day. The

United States must have understood that an attack might interrupt production,

which would in turn cause a large increase in the price of oil. Since

this would have a severe negative impact on the world economy, it would

further inflame anti-American sentiment throughout the world and even

turn U.S. voters against the enterprise. The conclusion: Lost Iraqi production

had to be replaced. Thus, an agreement was reached with OPEC to stabilize

the markets by increasing production levels as needed.

In March 2003, the Saudi oil minister reassured the International Energy

Agency of Saudi Arabia's longstanding policy and practice of supplying

the oil markets reliably and promptly, and highlighted the collective

responsibility that producing countries have shown in addressing the concerns

of world oil markets. This was most likely viewed as a temporary measure,

as it was assumed that Iraqi production would be restored and expanded

rapidly after the United States took charge.

In addition to the impending interruption of Iraqi production, in early

2003 Venezuelan oil production was far below its OPEC quota due to a conflict

between populist president Hugo Chavez and the business community; Nigerian

production was also depressed by civil strife.

OPEC rose to the occasion (or, more likely, felt compelled to rise to

the occasion, given the huge U.S. military presence in the Persian Gulf

in preparation for war) and increased production by about 3.2 million

barrels per day--equivalent to the production of the Norwegian North Sea

sector--virtually overnight, more than compensating for lost Iraqi, Venezuelan,

and Nigerian production.

About 65 percent of the increase came from just two countries, Saudi Arabia

and Kuwait; Saudi Arabia alone contributed more than half and probably

controls what remains of any spare production capacity.

The critical role that OPEC, in particular Saudi Arabia, plays as the

swing producer for the world oil market is clearly evident from this episode,

which allows one to quantify the ability of the Saudis to affect the world

oil market and the world economy.

The U.S. assault on Iraq has not undermined the power of OPEC and Saudi

Arabia. On the contrary, it has if anything enhanced that power. This

will not change until Iraqi oil production significantly exceeds its pre-invasion

level. Thus, even in the short term, and on the most cynical level, U.S.

Iraq policy vis-à-vis oil has been a failure.

Oil supplies are finite and will soon be controlled by a handful of nations;

the invasion of Iraq and control of its supplies will do little to change

that. One can only hope that an informed electorate and its principled

representatives will realize that the facts do matter, and that nature--not

military might--will soon dictate the ultimate availability of petroleum.

Alfred Cavallo is an energy consultant based in Princeton, New Jersey.

1. T. Ahlbrandt (project leader), "The USGS World Petroleum Assessment

2000." The assessment is available at www.usgs.gov and on compact

disc. A detailed analysis using the assessment appears in Alfred Cavallo,

"Predicting the Peak in World Oil Production," Natural Resources

Research, 2002, vol. 11, pp. 187-195. Production statistics, based on

data from the International Energy Agency, are available in a variety

of trade publications, including Oil and Gas Journal, World Oil, and Petroleum

Economist.

2. The most popular method used to predict a peak in oil production is

in M. King Hubbert's monograph, Energy Resources: A Report to the Committee

on Natural Resources, National Academy of Sciences-National Research Council,

Publication 1000-D, December 1962. Hubbert noted that resource production

often (but not always) could be described by a logistic growth curve,

and used oil production records and estimates of proven oil reserves made

by the American Petroleum Institute's Committee on Petroleum Reserves

to estimate the year of U.S. peak production. Hubbert does not discuss

the assumptions implicit in his model, among which are stable markets,

excellent profitability, and affordable prices for oil. See also Colin

Campbell and J. H. Laherrere, "The End of Cheap Oil," Scientific

American, March 1998, pp. 78-83. The Oil and Gas Journal has also recently

published a series of articles discussing the future of petroleum and

its alternatives. See Bob Williams, "Special Report: Debate Over

Peak Oil Issue Boiling Over, With Major Implications For Industry, Society,"

Oil and Gas Journal, July 14, 2003.

© 2004 Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists