Collapse and Overshoot

Collapse, if and when it comes again, will this time be global. No longer can any individual nation collapse. World civilization will disintegrate as a whole. Competitors who evolve as peers collapse in like manner.

Collapse, if and when it comes again, will this time be global. No longer can any individual nation collapse. World civilization will disintegrate as a whole. Competitors who evolve as peers collapse in like manner.

--

Joseph A. Tainter, The Collapse of Complex Societies, 1988

http://energybulletin.net/23259.html

Published on 4 Dec 2006 by Energy Bulletin. Archived on 4 Dec 2006.

Closing the 'Collapse Gap': the USSR was better prepared for peak oil

than the US

by Dmitry Orlov

Date: Fri, 09 May 2008

Date: Fri, 09 May 2008

Quote of the day

From today's issue of Science...

Living Up to Ancient Civilizations

The Classical Period Of Greece And Rome lasted more than a thousand years (from about 750 BCE to about 400 AD). By contrast, the modern world, beginning with Columbus's discovery of America, has lasted just over 500 years.

As a result of overpopulation, overconsumption, global warming, and environmental degradation, it now looks increasingly likely that there will be a major societal collapse within the next 200 years. How ironic that a civilization capable of tracing the origin of the universe from 10-43 seconds after its formation and putting a lander on Titan does not have the rigor and self-discipline to sustain itself for as long as the ancients managed to do.

- Geoffrey P. Glasby

Department of Geochemistry, GZG

University of Göttingen

Goldschmidtstrasse 1, D-37077, Germany

Interview with Jared Diamond:

www.earthfiles.com/news/news.cfm?ID=871&category=Environment

[excerpt]

HAVE YOU TALKED OFF THE RECORD WITH SOMEBODY WHO IS DEALING AT THE GLOBAL ECONOMIC LEVEL. I'M THINKING OF PAUL VOELKER. [Chairman of the U. S. Federal Reserve during the Jimmy Carter Administration, 1976-1980.) HE RECENTLY WROTE AN ARTICLE HAVING TO DO WITH HIS FEAR THAT THE DOLLAR COULD START GOING INTO A FREE FALL COLLAPSE WITHIN FIVE YEARS OF 2005, WHICH WOULD BE BY 2010. IT HAS TO DO WITH A SHIFT IN GLOBAL ECONOMIES TO THE EURO AND OTHER CURRENCIES AND ISSUES AROUND PETROLEUM. HAVE YOU TALKED WITH ANYONE ABOUT THAT?

Yes. I have not talked with Paul Voelker, but with other economists. I have had discussions with the famous economist, Jeffrey Sachs, at Columbia University. His point of view is very similar to mine. He regards as the biggest economic problem in the world today the nexus between public health problems and environmental problems and population problems. He has been going around the world advising countries about how to improve their economies, but also talking to First World countries about the importance of solving these problems.

Another person I've talked to is a (Bush Administration) cabinet minister who I cannot name, but a cabinet minister of the current administration. This cabinet minister has a point of view that is very different from that of our president. This cabinet minister read my book, Guns, Germs and Steel and read my book, Collapse, and is convinced of the seriousness of these problems.

The fact that an author of Diamond's caliber writes an (otherwise excellent) book on the collapse of civilizations without explicitly explaining peak oil gives you an idea of the extent to which we are fully and wholly unprepared in any fashion whatsoever to handle what has now become inevitable.

It also points to a rather disturbing possibility: future generations may not even be able to figure out what ultimately caused our collapse. They will point to symptoms such as terrorism, financial insolvency, poor leadership, etc. . . rather than understanding the fundamental driving force: resource depletion.

-- Matt Savinar, lifeaftertheoilcrash.net

www.energybulletin.net/4182.html

Published on Tuesday, February 1, 2005 by Museletter

Meditations on Collapse (a review of Jared Diamond's book)

by Richard Heinberg

Civilizations collapse. That is the rule that we learn from history, and it is a rule whose implications deserve careful thought given the fact that our own civilization-despite its global extent and unsurpassed technological prowess-is busily severing its own ecological underpinnings.

Thus we should pay close attention when Jared Diamond, one of the world's most celebrated and honored science writers, author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning Guns, Germs, and Steel, devotes his newest and already best-selling book to the subject of how and why whole societies sometimes lose their way and descend into chaos.

Diamond uses his considerable popular nonfiction prose-writing skills-carefully honed in the crafting of scores of articles for Natural History, Discover, Nature, and Geo-to trace the process of collapse in several ancient societies (including the Easter Islanders, the Maya, the Anasazi, and the Greenland Norse colony) and show parallels with trends in several modern nations (Rwanda, Haiti, and Australia).

One theme quickly emerges: the environment plays a crucial role in each instance. Resource depletion, habitat destruction, and population pressure combine in different ways in different circumstances; but when their mutually reinforcing impacts become critical, societies are sometimes challenged beyond their ability to respond and consequently disintegrate.

The ancient Maya practiced intensive slash-and-burn horticulture, growing mostly corn. Their population increased dramatically, peaking in the eighth century C.E., but this resulted in the over-cutting of forests; meanwhile their fragile soils were becoming depleted. A series of droughts turned problem to crisis. Yet kings and nobles, rather than comprehending and responding to the crisis, evidently remained fixated on the short-term priorities of enriching themselves, building monuments, waging wars, and extracting sufficient food from the peasants to support their ostentatious lifestyles. The population of Mayan cities quickly began a decline that would continue for several centuries, culminating in levels 90 percent lower than at the civilization's height in 700.

The Easter Islanders, whose competing clan leaders built giant stone statues in order to display their prestige and to symbolize their connection with the gods, cut every last tree in their delicate environment to use in erecting these eerie monuments. Hence the people lost their source of raw materials for building canoes, which were essential for fishing. Meanwhile bird species were driven into extinction, crop yields fell, and the human population declined, so that by the time Captain Cook arrived in 1774 the remaining Easter Islanders, who had long since resorted to cannibalism, were, in Cook's words, "small, lean, timid, and miserable."

Regarding the Anasazi of the American Southwest, who left behind stone ceremonial centers that had been integrated into a far-flung empire, I can do no better than to quote Diamond's own summary:

"Despite these varying proximate causes of abandonments, all were ultimately due to the same fundamental challenge: people living in fragile and difficult environments, adopting solutions that were brilliantly successful and understandable in the short run, but that failed or else created fatal problems in the long run, when people became confronted with external environmental changes or human-caused environmental changes that cities without written histories and without archaeologists could not have anticipated."

A second important theme in the book is that human choice can make the difference between prosperity and ruin. Diamond is quick to point out that he is not an "environmental determinist": while the leaders of the Maya and Easter Islanders made disastrous decisions that plunged their societies into collapse, others did better. He describes how the Inuit in the Arctic and Polynesians on Tikopia managed to create ways of life that were indefinitely sustainable, and why the Dominican Republic has had a more peaceful and economically stable history than its neighbor, Haiti.

Diamond argues that our modern global industrial society is creating some of the very same sorts of environmental problems that caused ancient societies to fail, plus four new ones: "human-caused climate change, buildup of toxic chemicals in the environment, energy shortages and full human utilization of the earth's photosynthetic capacity." Echoing the conclusions of the Limits to Growth study of 1972, Diamond notes that many of these problems are likely to "become globally critical within the next few decades."

There is much to admire in this book. Diamond's essential message-that our very persistence as a civilized society may depend upon well-led efforts to reduce the negative impact of our economic processes upon nature-is one that more people desperately need to hear. The author artfully skewers classic one-liner objections such as, "The environment has to be balanced against the economy," "Technology will solve our problems," and "If we exhaust one resource, we can always switch to some other resource meeting the same need." Collapse draws the reader into rich and fascinating discussions of specific modern instances in which collapse in some form already has occurred, is occurring, or is likely to occur-Rwanda, Haiti, and Montana-showing in each instance how political and economic events, emerging from underlying environmental crises and constraints, can lead to economic reversal, social disintegration, or even genocide.

Yet while this is a helpful discussion of the subject for readers who have never before contemplated the possibility that modern fossil-fuel-based industrialism may be unsustainable in the starkest meaning of the term, for readers who have been contemplating that fact for some time-and especially for those who have already made some efforts to draw parallels between the exuberance of modern industrial society and the similar qualities of ancient empires in their florescent stage immediately before their demise-Diamond's efforts fall short.

While the book is rigorous in detail, it is haphazard with regard to theory. Diamond's methodological prowess shines, for example, as he investigates the reasons for the failure of the Viking colony in Greenland: he uses the most recent archaeological data to build a careful, persuasive case that the Norse farmers simply failed to adjust their cultural attitudes to take advantage of the most abundant local protein source-fish-and hence starved. In the process, we learn a great deal about how these people lived, and about how archaeologists gather and piece together evidence in order to arrive at conclusions about the human past. Details matter, and Diamond is very good at moving beyond superficial similes ("America is like Rome prior to its fall") to look at particular places with care and nuance.

However, when presented with such a sweeping title and subject, readers need breadth of overview as much as depth of specificity. Why did the author select the examples he did? Why did he not choose to discuss Imperial China or Rome, or the ancient Mesopotamians or Egyptians? Why not, in addition to a thorough discussion of a few emblematic societies, also offer a comprehensive and systematic survey of all previous civilizations? This is not as daunting a prospect as it might seem: there have only been about 24 civilizations in all of human history (if we define civilization as a society with cities, writing, full-time division of labor, and relatively high levels of technological complexity). The wealth of data available would permit a fascinating comparative overview using a range of selected criteria.

Diamond refers on only three occasions (and then briefly) to Joseph Tainter' s classic The Collapse of Complex Societies (Cambridge University Press, 1988), which is widely considered the standard work on the subject. He rightly criticizes Tainter for underemphasizing the role of environmental fa ctors-especially resource depletion-in previous instances of collapse. However, Diamond does not take the time to explain Tainter's valuable contributions to the discussion. It is difficult for the reader to have the sense of building on a previous theory without an understanding of what the previous theory is. Theory was in fact one of the great strengths of Tainter 's book: he surveyed all known complex societies, and systematically assessed dozens of prior serious discussions of collapse (including the ideas of Arnold Toynbee, Elman Service, Pitirim Sorokin, and Alfred Kroeber), so that when he got around to introducing his own hypothesis (which can be summarized as the inevitability of the diminishing of returns on societal investments in complexity) the reader felt a sense of participation in the refinement of our collective understanding of the problem. This doesn't happen to nearly the same degree in Collapse. Why? Perhaps Diamond was trying to avoid sounding academic and wanted to write in such a way that the maximum number of readers would commit themselves to the task of wading through a long book on a dreary subject. But something was sacrificed in the process.

Important contributions to the discussion about collapse have been made since the publication of Tainter's magnum opus; one that comes readily to mind is John Michael Greer's paper "How Civilizations Fall: A Theory of Catabolic Collapse," with its distinction between maintenance collapse, in which a society recovers and again achieves imperial status, and depletion collapse, in which disintegration is complete and final. Greer's essay-which he has encountered some difficulty in placing in a peer-reviewed journal (it is currently archived at www.museletter.com)-contains significant theoretical insights, though it comes from a relatively unknown researcher working with easily available historical materials. One cannot help but wonder why Diamond, with the considerable resources of a major publisher and willing graduate students, could not have done much more to advance the theory of collapse.

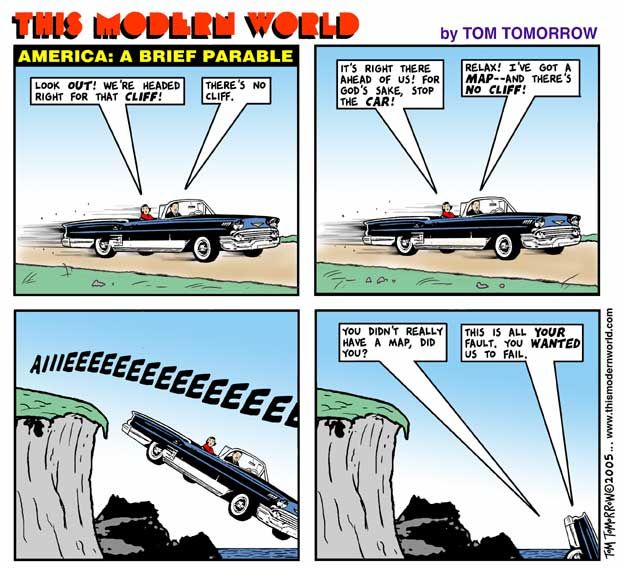

A second disappointment that readers already familiar with the subject matter may encounter with Collapse is the perception that, while the author is warning us that modern industrial civilization may be headed the way of the Classic Maya or the Easter Islanders, he seems satisfied with this warning. He offers, in essence, a message of the type we have come to expect: Humanity is undermining its ecological viability, but there are things we can do to turn the tide. Indeed, Diamond predictably devotes the last section of his last chapter to "reasons for hope," leaving the reader with evidence for thinking that collapse will not occur in our own instance after all. This excuses him from asking a question that appears to be tugging at more minds, and with more urgency, every day: What if it's already too late? Yes, if collapse can be averted, we should of course be working toward that end. But suppose for a moment that we have passed the point of no return, and that some form of collapse is now inevitable. What should we be doing in that case?

If we simply regard the question as unthinkable (because its premise is itself unthinkable), then we foreclose a discussion that could be extremely important. In a moment I intend briefly to state three good reasons for thinking that collapse is in fact unavoidable at this point. But even if there is only a moderate likelihood that industrial society is headed toward history's dustbin, shouldn't we be devoting at least some mental effort toward planning for a survivable collapse? Shouldn't we be thinking about what needs to be preserved so that future generations will have the information, skills, and tools that they need in order to carry on?

Here are my three reasons for concluding that Diamond has in fact made an extremely timid case for the likelihood of global industrial collapse; there are certainly others.

1. Diamond does not even hint at the phenomenon of the imminent global oil production peak. Even though he cites Paul Roberts' book the End of Oil and Kenneth Deffeyes' Hubbert's Peak in a note on page 551, he shows no understanding whatever of these authors' work. There is no discussion of the fact that oil production capacity is declining rapidly in nearly two dozen countries, while the world's reliance on oil for its essential energy needs continues to grow with each passing year. This is not a minor oversight. At least four independent studies now forecast that the global oil peak is likely to occur as soon as 2005 and probably before 2010, which means that there will not be enough time to invest in replacement energy sources before the decline begins; nor can we be assured that adequate replacement energy sources exist. In the estimation of a growing chorus of informed observers, the oil peak is likely to be a trigger for global economic crisis and the outbreak of a series of devastating resource wars.

2. At the same time, the global economic system and the world's monetary system are becoming increasingly dysfunctional for other reasons. Currently, the US dollar functions as the global reserve currency, and the dollar (like most other currencies) is loaned into existence at interest. This means that continual economic growth is structurally required in order to stave off a currency crash. Yet infinite growth within a closed system (e.g., the Earth) is impossible. So how long can growth continue? There are strong signs that the American economy, and hence that of the entire world, is headed soon toward a "correction" of unprecedented proportions. US debt (in the forms of consumer debt, government debt, and trade deficits) is at truly frightening levels and the American mortgage and real estate bubbles appear ready to burst at any moment. If one looks deeper, there are still other reasons to conclude that the global economy has nearly reached fundamental and non-negotiable restrictions on expansion. In his book The Limits of Business Development and Economic Growth (Palgrave Macmillan, 2005), business strategist Mats Larsson makes the point that most of technology and business development in the past has had as its goal the reduction of time and cost in manufacturing. But nothing can be done at less than no time or at less than no cost. He cites the example of the printing and distribution of books and other written media: with these, Gutenberg famously reduced time and cost. Now, the Internet enables the electronic reproduction and distribution of books, films, and music at almost no cost and in almost no time. Similarly, labor cost in China is probably now at close to the absolute theoretical minimum. Larsson's conclusion is that economic growth is perilously close to its ultimate bounds, even when resource constraints are not factored into the calculation.

3. Averting collapse would require changes that must be championed and partly implemented by political leaders: unprecedented levels of national and international cooperation would be needed in order to allocate essential resources in order to avert deadly competition for them as they become scarce, and our economic and monetary systems would have to be reformed despite pressure from the entrenched interests of wealthy elites. Yet the American political regime-the most important in the world, given US military supremacy and economic clout-has evidently become terminally dysfunctional, and is now the province of a group of extremist ideologues who apparently have virtually no interest in international cooperation or economic reform. This is a fact widely recognized outside the US, and by many sober observers within the country. The problem is not merely that politicians are being bought and sold by corporations (this has been going on for decades), but that the entire system has been hijacked by partisans who pride themselves on making decisions solely on the basis of ideology and in supreme disdain for "reality." At the same time, the US electoral system has been eviscerated and commandeered by a single party (using various forms of systematic fraud that have now become endemic), so that a peaceful rectification of the situation by a vote of the people has become virtually impossible. Moreover, the American media have been so cowed and co-opted by the dominant party that most of the citizenry is blissfully unaware of its plight and is thus extremely unlikely to vigorously oppose the current trends. Diamond shows some limited awareness of this truly horrifying state of affairs, and he realizes that wise political leadership would be essential to the avoidance of collapse. Yet he refuses to draw the obvious conclusion: the most powerful of the world's current leaders are every bit as irrational as the befuddled kings and chiefs who brought the Maya and Easter Islanders to their ruin.

None of these three problems can be solved quickly or easily if at all; each of the first two is by itself a sufficient cause for collapse; the third will effectively preclude any attempts to reverse the slide toward international chaos; and all three will no doubt rebound upon each other synergistically.

Diamond's subtitle, "How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed," implies that, for modern industrial societies, success is still an option. Yet if "success" implies the ability to maintain current population levels and current per-capita rates of consumption, then we may already have exhausted our choices. We cannot replace dwindling non-renewable resources, we cannot make industrial wastes disappear, we cannot quickly restabilize the global climate, and we cannot revive species that have become extinct.

What, then, are Diamond's "reasons for hope"? He offers only two: first, that our problems are, in principle at least, solvable; and second, that environmental thinking has become more common in recent years. But for hope to be realized, he says, modern societies will have to make good choices in two areas. We will need "courageous, successful long-term planning," which, he says, is indeed being undertaken by some governments and political leaders, at least some of the time. What Diamond doesn't mention is that the single instance of long-term planning that might have made all the difference to the survival of our civilization-a sustained choice by the US to wean itself from fossil fuels, beginning in the 1970s at the time of the first oil shocks-was not followed through; as a result, economic crises and resource wars are now virtually assured. We will also, he says, need to reconsider some of our core values, and he cites a few examples of modern societies that have done this (e.g., over two decades ago China decided to restrict the traditional freedom of individual reproductive choice). However, Diamond may be underestimating the degree to which some of the "values" that we would have to change (such as our mania for continuous economic growth) are not mere preferences or easily reversible government policies, but necessities structurally reinforced by multiple layers of institution, privilege, and power.

Perhaps the message of Collapse would have had more of a cutting-edge quality if the book had appeared in the early 1970s, when mere warnings were appropriate. Collapse might have added to the chorus of voices raised on the first Earth Day, and might have helped drive home the importance of the often-misrepresented Limits to Growth study.

Today, however, we are living in a different era. Collapse has, in effect, already begun, even though we have seen only the first of the trigger events that will eventually rivet public attention on the cascading process of disintegration taking place around us. The question is no longer that of avoiding collapse, but rather of making the best of it.

One of the many virtues of Joseph Tainter's book was that he dissipated some of the pejorative cloud surrounding the word collapse, defining it simply as a reduction in social complexity. This helps us to see that the process can manifest in different ways: it can occur slowly or quickly (usually the process takes decades or even centuries); it can be complete or partial; and it can be controlled or chaotic. Such an understanding leads one to envision the possibility of a managed collapse.

Given Jared Diamond's emphasis on choice, it might have been helpful if he had studied what people chose to do during previous periods of collapse, and how certain actions helped or hindered personal survival and the survival of culture.

In our own instance, efforts to manage the collapse might take several forms. Initial work along these lines might be indistinguishable from actions taken to try to prevent collapse-the sorts of things many people have been doing at least since the 1970s: the active protest of war, the protection of ecosystems and species, the defense of indigenous and traditional cultures, and the adoption of lifestyles of voluntary simplicity.

Then, as fossil-fuel-based support infrastructures began to disintegrate, other strategies might come to the fore: efforts to re-localize economies, to build intentional communities, and to regain forgotten handcraft skills. Like the European monks of the Middle Ages, forward-thinking groups with useful knowledge and abilities could build cultural lifeboats-communities of preservation and service that help surrounding regions cope with change and stress.

It would be foolish to assert that such a program could avert all of the potholes on the road down to a sustainable level of societal complexity; however, if we do not make efforts to manage the process of economic and societal contraction, it is easy to imagine collapse scenarios that would be hellish indeed.

One hesitates to criticize too harshly a book that tries to tell the world a truth that all too many refuse to hear. And yet this isn't the book that it could have been. At this point in time, we could stand a prominent book by an important author that finally announces what so many of us know all too well: collapse has begun.

Such a message need not be fatalistic in tone, because fatalism implies absence of choice. Diamond is right: we always have some control over events, or at least our response to events. The choice we have now is not as to whether our society will collapse, but how. Ladies and gentleman, the ship is sinking. I suggest that we set aside our immediate plans and consider how best to proceed, given the facts.

--

Richard Heinberg is the author of Powerdown: Options and Actions for a Post-Carbon World and The Party's Over: Oil, War and the Fate of Industrial Societies; he is a Core Faculty member of New College of California in Santa Rosa.

www.counterpunch.org/sale02222005.html

February 22, 2005

Imperial Entropy

Collapse of the American Empire

By KIRKPATRICK SALE

Don't Be Fooled: Advanced and Rational Societies Can Commit Environmental

Suicide

By Johann Hari

The Independent UK

Wednesday 08 June 2005

The way our economy is structured actually encourages environmental destruction.

When Tony Blair flew to Washington on Monday to discuss the rapid changes to the earth's climate caused by man, it is a shame he could not make a pit-stop on Easter Island. True, it is several thousand miles out of the way, and the carbon emissions from the flight would have been a further act of ecological destruction - but Easter Island is the most vivid illustration of the stakes human beings face.

The grimacing statues of Easter Island have - over the past 2000 years - witnessed the purest example in history of human beings committing unwitting environmental suicide. The story is startlingly simple: the human settlers on the island - living in perfect isolation from the rest of the world - systematically destroyed their own habitat. In a burst of over-development, they cut down their forests much faster than they could grow back. The result? At first, the island was plunged into war as different groups scrambled to seize the remaining natural resources for themselves. They turned on their leaders and staged revolutions, enraged that they had been misled into such a disaster. They even toppled some of their famous statues, symbols of the despised former chiefs. And then - finally - they were left with nothing. They went slowly mad, committed mass cannibalism, and almost completely died out.

In his chilling new book Collapse - How Societies Choose to Fail or Survive, the Pulitzer-prize winning geographer, Jared Diamond, describes how some of the most advanced civilizations in history - like the Maya - committed ecocide without realizing it. "What," he asks, "were Easter Islanders saying as they cut down the last tree on their island?" He dryly wonders if they said - as George Bush effectively does now - "Jobs not trees!", or "Technology will solve our problems; never fear, we'll find a substitute for wood." Perhaps they said, "We need more research, not scare-mongering! What are you, some kind of anti-Easter Island fanatic?"

It's a cute analogy, but the world of Bush and Blair is an infinity away from these pre-modern disasters, isn't it? I would like to think so - but, according to the world's leading climatologists, we must stop kidding ourselves. Ecocide has happened before to advanced, rational societies, and it can happen again. They warned yet again this week that we seem to be five minutes away from environmental midnight, and are now on-course for the most rapid increase in global temperatures since the last Ice Age.

And Easter Island is salient for another reason. When the Islanders' environment collapsed, they had nowhere to go; they were an isolated island cut off from the rest of the world. Now - for the first time - we have a global society where we are all dependent on each other. There are no alternative environments, no human settlements beyond the reach of the decisions we make. If our environment collapses, the human game is up. As Diamond puts it: "For the first time in history, we face the risk of a global decline." In this sense, we are all Easter Islanders now.

Of course, the ultimate fate of the islanders is only the most extreme possible end-game for global warming. (Even the Pentagon, however, has mapped out the possibility of this scenario unfolding globally in the 21st century, in a report leaked last year). More likely is that environmental damage - unless it is reversed now - will cause a drastic fall in living standards and rapid shifts in the way we live. It is a recipe to Make Poverty the Future.

Yet the Easter Islanders were not incomprehensibly mad. Like all societies that unknowingly commit collective suicide - from the Maya to Norse Greenlanders - they became afflicted with dozens of symptoms, each of which seemed understandable at the time. They might sound familiar. One is simple denial. They said: surely it can't be this bad? Doesn't it always work out in the end? Aren't we decent people? This mentality is common in Bush' s Republican Party, with swathes of oil cash and bogus research to reinforce it. Another problem is group-think: if everyone else is doing it, why shouldn't I? Why should I be the one who has to stop?

But the biggest common factor in past ecocides has been the pursuit of short-term "rational bad behavior" arising from clashes of interests between people. For example, one logging company decides to destroy great chunks of the Amazon, on the grounds that if they don't, some other logging company will. It seems rational, but it places the transitory and fragmentary interests of the individual or group ahead of the long-term interests of us all. Destroying forests leads in the long-term to a hideously irrational outcome for the world at a time when we need all the carbon sinks we can find.

The way our economy is currently structured actually encourages this environmental destruction. Try finding out how to get from London to Edinburgh: you'll find that the most environmentally disastrous form of travel (flight) is the cheapest, while the least damaging (train) costs a fortune. This model is now spreading across the world.

So what can we do? Despair would be foolish, and a gift to the environmental vandals; the solutions are all around us. For example, the British government has announced that the G8 summit will be "carbon neutral": the 4000 tonnes of carbon dioxide released will be counterbalanced by the planting of trees in Africa that will absorb the same amount.

It's a smart gesture, but if the Prime Minister really wants to deal with climate change, he should introduce legislation to make all our air travel carbon neutral. It's simple: if you want to get a flight, you should also have to pay the cost of the carbon debt you are building up by paying for trees in Africa.

Some environmentalists call this "true cost economics": instead of only paying the market price, you also pay the environmental price for your actions. This would roughly double the cost of air travel. Yes, that would be a pain, but dealing with runaway climate change will cause far more grief.

It will take dozens of tough political decisions like this to fend off disaster, but whenever these ideas are put to the Prime Minister, he says they are morally attractive but "politically impossible." Can't he see this is a classic example of "rational bad behavior"? The British government is currently making plans for a massive expansion of flight-paths and airports, and last year, this country's carbon emissions actually rose. We are still trapped in a destructive mindset, never mind the even-worse Americans. Recriminations against Bush aren't enough: we have been living beyond our environmental means for too long as well.

The long and winding road to Easter Island is far from inevitable; but every day we carry on polluting, we step further into the shadow of those dark granite statues.

from the December 28, 2004 edition

www.csmonitor.com/2004/1228/p15s01-bogn.html

How to succeed in history

Societies don't die by accident - they commit ecological suicide

By David Shi

Why did once flourishing societies collapse and disappear? Jared Diamond, a Pulitzer Prize-winning geographer at UCLA, has spent much of his career wrestling with this profound question. It is not merely a romantic mystery; the answers, he believes, offer us the prospect of self-preservation.

"Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed" is remarkable for its ambitious sweep and interpretive panache. Diamond studies four ancient societies across space and time: Easter Island in Polynesia, the native American Anasazi tribe in what is now the southwestern United States, the Maya civilization in Central America, and the isolated Viking settlement on the coast of Greenland. Although diverse in nature and context, these four societies experienced what Diamond calls "ecocide," unintentional ecological suicide.COLLAPSE:

How Societies Choose

to Fail or Succeed

By Jared Diamond

Viking

575 pp., $29.95For example, seafaring Polynesians settled on Easter Island 1,100 years ago. They cut the trees for canoes and firewood and used logs to help transport huge statues weighing as much as 80 tons. Eventually, they chopped down all the forests, and their society collapsed in an epidemic of cannibalism. By 1600, all of the trees and land birds on Easter Island were extinct.

"The parallels between Easter Island and the whole modern world," Diamond notes, "are chillingly obvious."

Diamond details how other societies pursued the same errors. But what makes the issue doubly fascinating is that some ancient cultures have found ways to persist for thousands of years. Japan, Java, and Tonga, for example, have flourished. What factors made some societies implode and others prosper?

Diamond, an evolutionary biologist trained in biochemistry and physiology, deftly uses comparative methods and multidisciplinary tools - archaeology, anthropology, paleontology, and botany - to marshal evidence that sustaining societies over time depends primarily on the quality of human interaction with the environment.

All of the vanished societies experienced environmental damage such as deforestation, soil erosion, the intrusion of salt water, or overhunting game animals. The second common factor was climate change, such as cooling temperatures or increased aridity. Add to that mix hostile neighbors, rapid population growth, and a loss of trading partners, and few societies can survive for long.

In each case, though, what ultimately caused ecocide was a series of flawed responses to societal crises. Environmental degradation does not ensure collapse. A society's fate, Diamond concludes, depends upon how it manages challenging situations.

He reveals, for instance, how the Vikings who settled in Greenland after AD 984 established a pastoral economy, raising sheep, goats, and cattle. They also hunted caribou and seal, and developed a flourishing trade in walrus ivory with Norway. But 300 years later, the Vikings vanished from Greenland. Documentary sources along with physical evidence reveal that their settlements gradually experienced deforestation and soil erosion. A colder climate in the 14th and 15th centuries impeded commerce with Norway and reduced the production of hay, which diminished their herds.

At the same time that the Vikings were being cut off from Norway, the Inuits began attacks on the Norse settlements in Greenland. Cultural prejudices prevented the Vikings from adopting Inuit technologies, such as harpoons, so they could not harvest whales. Nor were they willing to mimic the Inuits in developing dog sleighs, sealskin kayaks, and seagoing boats. As a result of these cultural prejudices, by 1440 the Vikings had all died out in Greenland, whereas the Inuits survive to this day.

Diamond's perspective is not solely historical. He also discusses contemporary developments in Somalia, Rwanda, Haiti, China, and Australia, as well as in Montana, a state that once was among the wealthiest in the nation but now struggles with poverty, population decline, and environmental problems.

Diamond complements his sobering analysis of collapsed civilizations with more uplifting examples of societies that have found ways to sustain themselves without overexploiting their environments.

What determines a society's fate, Diamond concludes, is how well its leaders and citizens anticipate problems before they become crises, and how decisively a society responds. Such factors may seem obvious, yet Diamond marshals overwhelming evidence of the short-sightedness, selfishness, and fractiousness of many otherwise robust cultures. He reveals that many leaders were (and are) so absorbed with their own pursuit of power that they lost sight of festering systemic problems.

Today, Diamond observes, the world is "on a nonsustainable course," but he remains a "cautious optimist." The problems facing us are stern, he notes, but not insoluble. They demand stiff political will, a commitment to long-term thinking, and a willingness to make painful changes in what we value.

The fact that the United States over the past 30 years has reduced major air pollutants by a quarter at the same time that energy consumption and population have risen 40 percent gives Diamond hope. So does the success of many nations in slowing their rates of population growth.

He concludes, "We have the opportunity to learn from the mistakes of distant peoples and past peoples." But the question remains, will we?

• David Shi is the president of Furman University in Greenville, S.C.

Disasters waiting to happen

The tsunami may have been an act of nature, but further environmental

catastrophes caused by humans will be much worse, says Jared Diamond

Thursday January 6, 2005

The Guardian

The events of Boxing day have shown us all how fragile our existence is. The tsunami was an unavoidable natural disaster, which could happen anytime. But not all disasters are so beyond our control. Our own actions may provoke global catastrophes just as forceful as those in the Indian ocean.

Take the human impact on sea levels. Imagine you live on an island safely 15 feet above sea level. If human-induced climate change raises those levels by only a few feet, the difference man has made could spell disaster in the event of a 12ft tsunami. We cannot stop another tsunami. But the threats of man-made environmental collapse are now more pressing than ever.

Ask some ivory-tower academic ecologist, who knows a lot about the environment but never reads a newspaper and has no interest in politics, to name the overseas countries facing some of the worst problems of environmental stress, overpopulation, or both. The ecologist would likely answer: "That's a no-brainer, it's obvious. Your list of environmentally stressed or overpopulated countries should surely include Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Burundi, Haiti, Indonesia, Iraq, Rwanda, the Solomon Islands, and Somalia, plus others".

Then ask a first world politician, who knows nothing and cares less about the environment and population problems, to name the world's worst trouble spots: countries where state government has already been overwhelmed and has collapsed, or is now at risk of collapsing, or has been wracked by recent civil wars; and countries that, as a result of those problems, are also creating problems for us rich first world countries. Surprise, surprise: the two lists would be very similar.

Today, just as in the past, countries that are environmentally stressed, overpopulated, or both, become at risk of getting politically stressed, and of their governments collapsing. When people are desperate, undernourished, and without hope, they blame their governments, which they see as responsible for or unable to solve their problems. They try to emigrate at any cost. They fight each other over land. They kill each other. They start civil wars. They figure that they have nothing to lose, so they become terrorists, or they support or tolerate terrorism.

The results of these transparent connections are far-reaching and devastating. There are genocides, such as those that exploded in Bangladesh, Burundi, Indonesia, and Rwanda; civil wars or revolutions, as in most of the countries on the lists; calls for the dispatch of troops, as to Afghanistan, Haiti, Indonesia, Iraq, the Philippines, Rwanda, the Solomon Islands, and Somalia; the collapse of central government, as has already happened in Somalia and the Solomon Islands; and overwhelming poverty, as in all of the countries on these lists.

Hence the best predictors of modern "state failures" prove to be measures of environmental and population pressure, such as high infant mortality, rapid population growth, a high percentage of the population in their late teens and 20s, and hordes of young men without job prospects and ripe for recruitment into militias.

Those pressures create conflicts over shortages of land, water, forests, fish, oil, and minerals. They create not only chronic internal conflict, but also emigration of political and economic refugees, and wars between countries arising when authoritarian regimes attack neighbours in order to divert popular attention from internal stresses.

In short, it is not a question open for debate whether the collapses of past societies have modern parallels and offer any lessons to us. Instead, the real question is how many more countries will undergo them.

As for terrorists, you might object that many of the political murderers, suicide bombers, and 9/11 terrorists were educated and moneyed rather than uneducated and desperate. That's true, but they still depended on a desperate society for support and toleration. Any society has its murderous fanatics; the US produced its own Timothy McVeigh and its Harvard-educated Theodore Kaczinski. But well-nourished societies offering good job prospects, like the US, Finland, and South Korea, don't offer broad support to their fanatics.

The problems of all these environmentally devastated, overpopulated, distant countries become our own problems because of globalisation. We are accustomed to thinking of globalisation in terms of us rich advanced first worlders sending our good things, such as the internet and Coca-Cola, to those poor backward third worlders. But globalisation means nothing more than improved worldwide communications, which can convey many things in either direction; globalisation is not restricted to good things carried only from the first to the third world. We in the US are no longer the isolated Fortress America to which some of us aspired in the 1930s; instead, we are tightly and irreversibly connected to overseas countries. The US is the world's leading importer nation, we import many necessities and many consumer products, as well as being the world's leading importer of investment capital. We are also the world's leading exporter, particularly of food and of our own manufactured products. Our own society opted long ago to become interlocked with the rest of the world. That's why political instability anywhere in the world now affects us, our trade routes, and our overseas markets and suppliers.

We are so dependent on the rest of the world that if, 30 years ago, you had asked a politician to name the countries most geopolitically irrelevant to our interests, the list might surely have begun with Afghanistan and Somalia, yet they subsequently became recognised as important enough to warrant our dispatching US troops. The US can no longer get away with advancing its own self-interests, at the expense of the interests of others.

When distant Somalia collapsed, in went American troops; when the former Yugoslavia and Soviet Union collapsed, out went streams of refugees to all of Europe and the rest of the world; and when changed conditions of society, settlement, and lifestyle spread new diseases in Africa and Asia, those diseases moved over the globe.

We need to realise that there is no other planet to which we can turn for help, or to which we can export our problems. Instead, we need to learn to live within our means.

B y world standards, southern California's environmental problems are relatively mild. Jokes by east coast Americans to the contrary, this is not an area at imminent risk of a societal collapse. Los Angeles is well known for some problems, especially its smog, but most of its environmental and population problems are modest or typical compared to those of other leading first world cities.

I moved here in 1966. Thus, I have seen how southern California has changed over the last 39 years, mostly in ways that make it less appealing.

The complaints voiced by virtually everybody in LA are those directly related to our growing and already high population: our incurable traffic jams, the very high price of housing, the long distances, of up to two hours and 60 miles one way, over which people commute daily in their cars between home and work. Los Angeles became the US city with the worst traffic in 1987 and has remained so every year since then.

No cure is even under serious discussion for these problems, which will only get worse. There is no end in sight to how much worse Los Angeles's problems of congestion will become, because millions of people put up with far worse traffic in other cities.

Environmental and population problems have been undermining the economy and the quality of life in southern California. They are in large measure ultimately responsible for our water shortages, power shortages, garbage accumulation, school crowding, housing shortages and price rises, and traffic congestion. However, there are many reasons commonly advanced to dismiss the importance of environmental problems. These objections are often posed in the form of simplistic one-liners. Here are some of the commonest ones:

"The environment has to be balanced against the economy"

This portrays environmental concerns as a luxury but puts the truth backwards. Environmental messes cost us huge sums of money both in the short run and in the long run; cleaning up or preventing those messes saves us huge sums.

Just think of the damage caused by agricultural weeds and pests, the value of lost time when we are stuck in traffic, the financial costs resulting from people getting sick or dying from environmental toxins, cleanup costs for toxic chemicals, the steep increase in fish prices due to depletion of fish stocks, and the value of farmland damaged or ruined by erosion and salinisation. It adds up to a few hundred million dollars per year here, a billion dollars there, another billion over here, and so on for hundreds of different problems.

For instance, the value of "one statistical life" in the US - ie, the cost to the US economy resulting from the death of an average American whom society has gone to the expense of rearing and educating but who dies before a lifetime of contributing to the national economy - is usually estimated at around $5m (£2.6m). Even if one takes the conservative estimate of annual US deaths due to air pollution as 130,000, then deaths due to air pollution cost us about $650bn (£340bn) per year. That illustrates why the US Clean Air Act of 1970, although its cleanup measures do cost money, has yielded estimated net health savings (benefits in excess of costs) of about $1 trillion per year, due to saved lives and reduced health costs.

"Technology will solve our problems"

Underlying this expression of faith is the implicit assumption that, from tomorrow onwards, technology will function primarily to solve existing problems and will cease to create new problems. Those with such faith also assume that the new technologies now under discussion will succeed, and that they will do so quickly enough to make a big difference soon.

But actual experience is the opposite. Some dreamed-of new technologies succeed, while others don't. Those that do succeed typically take a few decades to develop and be phased in widely: think of gas heating, electric lighting, cars and airplanes, television and computers.

New technologies, whether or not they succeed in solving the problem they were designed to solve, regularly create unanticipated new problems. Technological solutions to environmental problems are routinely far more expensive than preventive measures to avoid creating the problem in the first place: for example, the billions of dollars of damages and cleanup costs associated with major oil spills, compared to the modest cost of safety measures to minimise the risks of a major oil spill.

All of our current problems are unintended negative consequences of our existing technology. What makes you think that, as of January 1, 2006, for the first time in human history, technology will miraculously stop causing new unanticipated problems while it just solves those it previously produced?

A good example is chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs). The coolant gases formerly used in refrigerators and air conditioners were toxic and could prove fatal if the appliance leaked while the homeowner was asleep at night. Hence it was hailed as a great advance when CFCs (alias freons) were developed as synthetic refrigerant gases.

They are odourless, non-toxic, and highly stable under ordinary conditions at the Earth's surface, so that initially no bad side effects were observed or expected. But in 1974 it was discovered that in the stratosphere they are broken down by intense ultraviolet radiation to yield highly reactive chlorine atoms that destroy a significant fraction of the ozone layer protecting us and all other living things against lethal ultraviolet effects.

Unfortunately, the quantity of CFCs already in the atmosphere is sufficiently large, and their breakdown sufficiently slow, that they will continue to be present for many decades after the eventual end of all CFC production.

"We can switch to electric cars, or to solar energy"

Optimists who make such claims ignore the unforeseen difficulties and long transition times regularly involved. For instance, one area in which switching based on not-yet-perfected new technologies has repeatedly been touted as promising to solve a major environmental problem is automobiles.

The current hope for a breakthrough involves hydrogen cars and fuel cells, which are technologically in their infancy. Equally, there is the motor industry's recent development of fuel-efficient hybrid gas/electric cars. However, the automobile industry's simultaneous development of SUVs (Sports Utility Vehicles), which have been outselling hybrids by a big margin more than offset their fuel savings. The net result of these two technological breakthroughs has been that the fuel consumption and exhaust production of the American car fleet has been going up rather than down.

Another example is the hope that renewable energy sources, such as wind and solar energy, may solve the energy crisis. These technologies do indeed exist; many Californians now use solar energy to heat their swimming pools, and wind generators are already supplying about one-sixth of Denmark's energy needs. However, wind and solar energy have limited applicability because they can be used only at locations with reliable winds or sunlight.

The recent history of technology shows that conversion times for adoption of major switches, such as oil lamps to gas lamps to electric lights, require several decades. It is indeed likely that energy sources other than fossil fuels will make increasing contributions to our motor transport and energy generation, but this is a long-term prospect.

"The world's food problems will be solved by more equitable distribution and genetically modified (GM) crops"

The obvious flaw is that first world citizens show no interest in eating less so that third world citizens could eat more. While first world countries are willing occasionally to export food to mitigate starvation occasioned by some crisis (such as a drought or war), their citizens have shown no interest in paying on a regular basis to feed billions of third world citizens.

If that did happen but without effective overseas family planning programs, which the US government currently opposes on principle, the result would just mean an increase in population proportional to an increase in available food.

Genetically modified food varieties by themselves are equally unlikely to solve the world's food problems. In addition, virtually all GM crop production at present is of just four crops (soy-beans, corn, canola, and cotton) not eaten directly by humans but used for animal fodder, oil, or clothing, and grown in six temperate-zone countries or regions. Reasons are the strong consumer resistance to eating GM foods and the fact that companies developing GM crops can make money by selling their products to rich farmers in mostly affluent temperate-zone countries, but not by selling to poor farmers in developing tropical countries. Hence the companies have no interest in investing heavily to develop GM cassava, millet, or sorghum for farmers in developing nations.

"Just look around you: there is absolutely no sign of imminent collapse"

For affluent western citizens, conditions have indeed been getting better, and public health measures have on the average lengthened lifespans in the third world as well. But lifespan alone is not a sufficient indicator: billions of third world citizens, constituting about 80% of the world's population, still live in poverty, near or below the starvation level.

Even in the US, an increasing fraction of the population is at the poverty level and lacks affordable medical care, and all proposals to change this situation have been politically unacceptable. In addition, all of us know as individuals that we don't measure our economic wellbeing just by the present size of our bank accounts: we also look at our direction of cash flow.

When you look at your bank statement and you see a positive £5,000 balance, you don't smile if you then realise that you have been experiencing a net cash drain of £200 per month for the last several years, and at that rate you have just two years and one month left before you have to file for bankruptcy.

The same principle holds for our national economy, and for environmental and population trends. The prosperity that the richer nations enjoy at present is based on spending down its environmental capital in the bank. It makes no sense to be content with our present comfort when it is clear that we are currently on a non-sustainable course.

"Why should we believe the fearmongering environmentalists this time?"

Yes, some predictions by environmentalists have proved incorrect, but it is misleading to look selectively for environmentalist predictions that were proved wrong, and not also to look for environmentalist predictions that proved to be right, or anti-environmentalist predictions that proved wrong.

We comfortably accept a certain frequency of false alarms and extinguished fires, because we understand that fire risks are uncertain and hard to judge when a fire has just started, and that a fire that does rage out of control may exact high costs in property and human lives. No sensible person would dream of abolishing the town fire department just because a few years went by without a big fire. Nor would anyone blame a homeowner for calling the fire department on detecting a small fire, only to succeed in quenching the fire before the fire truck's arrival.

We must expect some environmentalist warnings to turn out to be false alarms, otherwise we would know that our environmental warning systems were much too conservative. The multi-billion-dollar costs of many environmental problems justify a moderate frequency of false alarms.

"The population crisis is already solving itself"

While the prediction that world population will level off at less than double its present level may or may not prove to be true, it is at present a realistic possibility. However, we can take no comfort in this possibility, for two reasons: by many criteria, even the world's present population is living at a non-sustainable level; and the larger danger that we face is not just of a two-fold increase in population, but of a much larger increase in human impact if the third world's population succeeds in attaining a first world living standard.

It is surprising to hear some first world citizens nonchalantly mentioning the world's adding "only" two-and-a-half billion more people (the lowest estimate that anyone would forecast) as if that were acceptable, when the world already holds that many people who are malnourished and living on less than $3 (£1.60) per day.

"Environmental concerns are a luxury affordable just by affluent first world yuppies"

This view is one that I have heard mainly from affluent first world yuppies lacking experience of the third world. In all my experience of Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, East Africa, Peru, and other third world countries with growing environmental problems and populations, I have been impressed that their people know very well how they are being harmed. They know it because they immediately pay the penalty, in forms such as loss of free timber for their houses, massive soil erosion, and (the tragic complaint that I hear incessantly) their inability to afford clothes, books, and school fees for their children.

Another view that is widespread among affluent first world people, but which they will rarely express openly, is that they themselves are managing just fine at carrying on with their lifestyles despite all those environmental problems, which really don't concern them because the problems fall mainly on third world people (though it is not politically correct to be so blunt).

Actually, the rich are not immune to environmental problems. Chief executive officers of big western companies eat food, drink water, breathe air, and have (or try to conceive) children, like the rest of us. While they can usually avoid problems of water quality by drinking bottled water, they find it much more difficult to avoid being exposed to the same problems of food and air quality as the rest of us. Living disproportionately high on the food chain, at levels at which toxic substances become concentrated, they are at more rather than less risk of reproductive impairment due to ingestion of or exposure to toxic materials, possibly contributing to their higher infertility rates and the increasing frequency with which they require medical assistance in conceiving.

In addition, in the long run, rich people do not secure their own interests and those of their children if they rule over a collapsing society and merely buy themselves the privilege of being the last to starve or die.

As for first world society as a whole, its resource consumption accounts for most of the world's total consumption that has given rise to the impacts described at the beginning of this chapter. Our totally unsustainable consumption means that the first world could not continue for long on its present course, even if the third world didn't exist and weren't trying to catch up to us.

"If those environmental problems become desperate, it will be at some time far off in the future, after I die"

In fact, at current rates most or all of the dozen major sets of environmental problems discussed at the beginning of this chapter will become acute within the life-time of young adults now alive.

Most of us who have children consider the securing of our children's future as the highest priority to which to devote our time and our money. We pay for their education and food and clothes, make wills for them, and buy life insurance for them, all with the goal of helping them to enjoy good lives 50 years from now. It makes no sense for us to do these things for our individual children, while simultaneously doing things undermining the world in which our children will be living 50 years from now.

This paradoxical behaviour is one of which I personally was guilty, because I was born in the year 1937, hence before the birth of my children I too could not take seriously any event (like global warming or the end of the tropical rainforests) projected for the year 2037. I shall surely be dead before that year, and even the date 2037 struck me as unreal. However, when my twin sons were born in 1987, I realized with a jolt: 2037 is the year in which my kids will be my own age of 50. It's not an imaginary year! What's the point of willing our property to our kids if the world will be in a mess then anyway?

About the author

Professor of physiology at UCLA since 1966, Jared Diamond developed a parallel career in the ecology and evolution of New Guinea birds while in his twenties, then added a professorship in geography when, in his fifties, his interest grew in environmental history. Boston-born son of a physician father and teacher/musician/linguist mother, he is a Pulitzer prize-winning author of bestselling books including The Third Chimpanzee and Why is Sex Fun?. He and his wife Marie Cohen, a clinical psychologist at UCLA David Geffen School of Medicine have twin 17-year-old sons. In his spare time he watches birds and is learning his 12th language, Italian.

Is Jared right?

The author of Collapse and Guns, Germs and Steel will be talking live online on Thursday January 20 at 3pm. Post your questions and messages for Jared Diamond now here.

Read part two of this article

· Extracted from Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Survive by Jared Diamond published by Allen Lane on January 17 at £20. To obtain a copy at the offer price of £18.40 with free UK postage call the Guardian book service on 0870 836 0875 or go to guardian.co.uk/bookshop

Ronald Wright: when CIVILIZATIONS collapse

Interview by Briony Penn in May 2005 - FOCUS (www.focusonline.ca)

COASTLINES: Writers, writing, and books from the West Coast and beyond

This winter, the 2004 Massey Lectures --broadcast to critical acclaim on CBC Radio --featured the work of historian and novelist Ronald Wright. He was chosen by the CBC and Massey College to expand on ideas developed in his award-winning fiction and nonfiction, such as A Scientific Romance, Stolen Continents and Time Among the Maya, writings that often explore historical and archaeological evidence for what causes the downfall of civilizations. The lectures are published under the title A Short History of Progress by Anansi Press. http://www.cbc.ca/ideas/massey/massey2004.html

<http://www.cbc.ca/ideas/media/2004_massey.ram>

Listen to A Short History of Progress Part One (real player)

Last year, Wright and his anthropologist wife Janice Boddy moved to Salt Spring Island, though Wright's forebears have lived in BC for a century. I first met Wright at a local government meeting, where he gave an impassioned speech urging local politicians to shut down an illegal quarry operating in the headwaters of a watershed near his home. In between protests and stops on his book tour across North America, Wright and I discussed the ideas in his book and how they influence his local activism.BP: What is A Short History of Progress about?

RW: The title is deliberately playful in that human progress often turns out to have a short history. Most civilizations last about 1000 years from start to finish, as did the Sumerians, Easter Islanders, Maya and the Romans, all of whom I looked at in the book. Some go more quickly and a few survive longer, but as a general rule of thumb, 1000 years is all they last. And that isn't a very long period given that modern humans --people exactly like ourselves-- have existed for more than 100,000 years.

BP: The premise of the book is that civilizations keep falling into what you call "progress traps." What are they?

RW: A progress trap is something that starts out as a good idea but ultimately leads people down a dead end.

Take a seductive idea like irrigation, which in the short-term is a good thing. People benefit from the idea, but in the long term it proves disas¹trous, which is what happened to the Sumerians. They invented irrigation to grow wheat in the desert, but what they didn't realize is that the salt was getting left behind in the soil as the water evaporated in the hot sun. Over centuries, their fields turned saline, their yields declined and they had to switch crops. In the end, their civilization fell because they'd ruined their land. That is a classic progress trap, and history is full of them.

BP: You started off as a student of archaeology; is that what got you looking at the collapse of civilizations?

RW: Obviously, archaeologists are dealing with failed civilizations. When you see ruins, it's usually because people screwed up in some way. One of the civilizations I studied as a graduate student was the ancient Maya in Guatemala and southern Mexico. They are another classic case of people who had a brilliant civilization, which collapsed due to the overuse of the environment and overpopulation.

I came to realize that we seem to be doing the same thing on a worldwide scale as these ancient civilizations did in their small parts of the world. Then, they were more or less isolated from each other, so if they destroyed their local envi¹ronment, people elsewhere could carry on. Now, we have just one big civilization.

BP: Why do you refer to civilizations as "the great experiment?"

RW: The great experiment is the "invention" of agriculture-actually it was an accident, or series of steps-which allowed civilizations to arise. I mean civilization in the anthropological sense--big societies with large populations, cities, temples, kings, professions, armies and state¹level organization.

The past shows us that the experiment tends to work well for a while, then fails. Now, because the whole world is interdependent through international trade, all our eggs are in one basket. This is very dangerous. The experiment has been too successful. There are more than six billion people on this planet, four times the number that existed only a century ago.

BP: You attribute the problem to the fact that our cultural evolu¹tion has outstripped our physical evolution. What do you mean?

RW: Biological change is slow. We have not changed physically, either in our skeletal structure or in the size of our brain, for at least 50,000 years. We evolved as ice-age hunters. The change in our ways of life since then is through the growth of culture, and the ability to pass on the growing complexity of knowledge from generation to generation. You could say that culture is our "software." So we are running 21st century software on hardware last upgraded 50,000 years ago. That's part of our trouble. We are smart enough to get ourselves into trouble, but not smart enough to get ourselves out of it.

Culture is accelerating. The amount of cultural change in a decade now is far more than the change of a lifetime two centuries ago. We can't see far enough ahead to control or even foresee the consequences of what we are doing.

What really worries me, and is at the heart of this book, is the idea that change is running out of control. We no longer have control over our technologies, or our population. We keep inventing new technologies, such as genetic engineering, or before that, atomic weapons and power, whose consequences we can neither control nor foresee. We have a hard time giving up our toys.

BP: Given that we have the minds of Paleolithic hunters and gatherers, what is it about our minds that leads us so easily into these progress traps?

RW: I think it is the difference between short-term and long-term thinking. We tend to hope for the best and think that things will turn out well. If we've -had one good year or one technology has served us well, we think next year will be even better.

Evolution has produced a creature that has benefited from being extremely good at solving short-term problems. As hunters, we are very clever at ambushing game, but not so clever at long-range planning. The Sumerians didn't see that their fields were going to salt up. Even when they did understand the trouble, they failed to make intelligent adjustments towards conservation, to reduce the load on nature of their extravagant building projects. They didn't do that, nor did the Maya, nor the Romans.

The only thing that saved the Egyptians and the Chinese was their generous ecologies, like the annual flooding of the Nile, that subsidized their mistakes. Civilizations have gone full throttle, hoping nature will take care of itself. Our inherent flaw is that we just aren't careful enough.

BP: It seems to be extraordinary that we have been so seduced by the great experiment. As the archaeological record suggests, civilization for the vast majority of people meant harder work, more monotonous work, less leisure time, less security, and we lived shorter lives with a less nutritious diet, so why did we change?

RW: People didn't have a choice once they started down that path because the first progress trap was the perfection of hunting. Upper Paleolithic hunters got so good that they were killing game faster than it could breed¹they were already spending nature's "capital," not the interest on the capital. So they got caught in this trap that as they became better hunters, they were putting more food on the table. This led to the women having more babies so they had to go out and kill more game. When they got to the stage of over-killing the game, the survivors were forced to look for new food sources. Gathering developed into gardening and gardening developed into large-scale agriculture. As people switched, the food supply did increase but it was more monotonous and less diverse. At that point, there was no going back; for everyone except the upper classes, the natural diversity of wild food was gone.

BP: That is an interesting fact-that there hasn't been been one new staple food crop developed since the Neolithic.

RW: All of the big food crops that feed us today (wheat, corn, potatoes, rice, etc.) were developed by prehistoric people in the early stages of the development of civilization. For all the boasting about the new varieties of the green revolution in the 1960s, or genetically modified organisms of today, modern scientists have not developed a single staple crop from scratch.

BP: In addition to not being able to think long-term, you also state that we have an evolutionary weakness for "ideological pathologies." What does that mean?

RW: There is a susceptibility of human societies to crazy delusions. These tend to be of a religious nature and anthropologists call these delusions, or runaway ideas that cause problems, "ideological pathologies."

One example would be the way the Easter Islanders devoted all the resources from their small island to putting up statues to their ancestors. It got to the point where they were prepared to cut down the last tree to put up the last statue and not save any trees even for canoes to leave the island. After deforestation and population collapse, they had few options but cannibalism. They had been seduced by this mania.

It is easy to say, "Well yes, they were primitive people," but right now, we are seeing the same thing happening amongst the religious right in the most powerful nation on Earth, the United States. Back in the Reagan administration, the Secretary of the Interior got up in front of Congress and said, "You don't have to worry about passing laws to save the environment because it won't be long before the Lord returns." These ideas are very much at work in the Bush administration too. There is an enormous influence from fundamentalist messianic Christians who think God will come down and clean up our mess. I don't want to dump on anyone's religion, but when delusions like this dictate public policy, they are extremely dangerous.

BP: Why is it that civilizations, like the Romans, tend to shift from democratic republics to empires as resources get low?

RW: The American Republic seems to be more or less where the Roman Republic was when Caesar came along. When democracies embark on conquests, you often see democratic institutions withering and power passing into military hands. The Americans are trying to impose their will all over the world, and that is imperialism. While focusing on terrorism and national security, they are ignoring the real problems posed by the progress traps we are walking into.

If we had a catastrophic nuclear war, for example, we will have a trap snapping shut on us in minutes. Even without that, we have depletion of fisheries and farmland, pollution of land and water, overpopulation, with half the world living in unhealthy malnourished conditions --a petri dish for growing new diseases, obscene amounts of money going into fewer hands and being used for military projects like the missile defense shield.

We are doing all the wrong things and making all the same mistakes as those arrogant Maya kings and mad Roman emperors. We've done it all before. I could describe my book as a police profile of a repeat offender.

BP: What about the response from the right, arguing that everything's fine?

RW: You don't have to take my word that it's not. The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment Report came out recently. This was a report put together over the last five years by 1300 scientists from 95 nations. This isn't something from greeny leftwing organizations; the US, UN and World Bank are involved. Their findings are frightening and very sobering. For example, nearly two-thirds of the world's ecosystems are already seriously degraded, 90 percent of fish are already gone from the oceans. Climate change is a huge worry because we are destabilizing the Earth's climate, which can lead to widespread crop failure. Extreme weather in several breadbasket regions such as the prairies could lead to worldwide hunger.

BP: What do you think about Vancouver Island's resistance to collapse?

RW: We used to have enormous marine resources, but we have done terrible things to them by silting up rivers from clear-cutting and releasing parasites from fish farms. Although we have lots of water and a mild climate, we don't have a lot of farmland. We are in the same situation as a country like Peru, where only a tiny percentage of the land is arable. The ancient Inca empire was smart enough to know that you don't build on that farmland. We are doing exactly the opposite, allowing urban sprawl. The best land in Canada is disappearing under shopping malls and subdivisions. That is a really dumb mistake. All the civilizations that have done that in the past have crashed, and they deserved to.

BP: Through the experiences of places like Easter Island we know that islands are particularly vulnerable. What are your thoughts about the long-term prospects of the island you live on, Salt Spring Island?

RW: There are lots of good things happening on Salt Spring, but even here you have people making terrible uses of the land. Right nearby, someone has been operating an unlawful quarry on a residential lot and blasting away acres of hillside. This sort of thing destroys natural vegetation and wildlife habitat, it causes topsoil to erode and silt up creeks, contaminating drinking water. Even though the local government, the Islands Trust, has a mandate "to preserve and protect," it has shown lethargy and cowardice on this issue for years. If we can't organize our own little societies here in the Gulf Islands, in a country as lucky and well-educated as Canada, to be law-abiding and to use our land wisely and hand it down to future generations in a healthy state, then what hope is there for the rest of the planet?

BP: But you say in the concluding chapter of the book that hope is part of our problem in that it drives us to invent new fixes for old messes, which in turn create ever more dangerous messes, so what do you mean by that?

RW: Irrational hope --merely hoping for the best instead of acting for the best-- is what I mean there. We need to wake up and realize that we are driving far too quickly for the range that we can see ahead. We need to make do with what we have, rather than hoping for some new way to hit the jackpot. This means redistributing the surplus wealth that is going to space weapons, unnecessary wars and ridiculously large salaries for heads of corporations.